Images have long been central to how architecture is imagined, conveyed, and remembered. They’re the first glimpse, the persuasive tool, sometimes even the main event. As a medium, they’ve evolved with the discipline, stretching from the Renaissance, where drawing formalized through perspective, to the industrial age, when mass printing and photography gave architectural images a broader reach and commercial force.

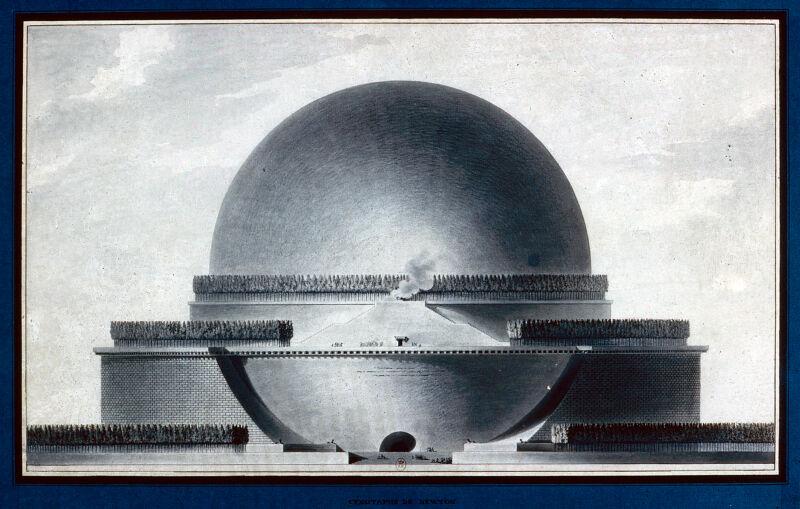

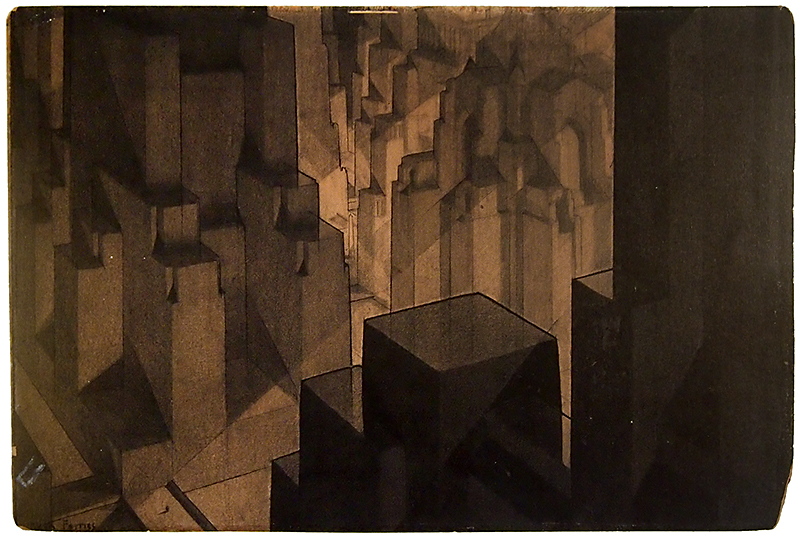

In the 18th century, architects like Étienne-Louis Boullée crafted visionary renderings of impossible buildings—vast cenotaphs and sublime geometries that couldn’t be built but lingered precisely because of their image. These drawings weren’t construction documents but ideas, staged with shadow and scale to move the imagination. They belonged more to painting than to building1. Fast forward to the 20th century, and the image began to shift again. Archigram’s speculative collages redefined the architectural drawing, turning it into a graphic manifesto2. Their urban futures weren’t drawn for the permit office but for the page, the gallery wall, the public eye. Around the same time, Mies van der Rohe’s iconic photomontage of a Berlin skyscraper—never built—was less about technical clarity and more about impact, atmosphere, and presence3. These images carried weight not because they described built form, but because they shaped architectural discourse.

That separation still defines the architectural image today. Renderings, animations, and digital composites are often scaleless, flat, and atmospheric. They don’t invite measurement so much as mood. They bypass technical legibility in favor of quick visual understanding. And in a culture dominated by screens, this has only intensified. Architectural discourse now unfolds through feeds and stories, driven by aesthetics, trends, and clicks. Architects are caught between two modes of image-making: the dreamy, stylized render that circulates like cultural capital, and the precise, utilitarian image tied to delivery and execution. One builds narrative, the other builds buildings. Both are necessary, but they rarely overlap. We no longer ask just what a building looks like, but how it photographs, renders, and performs as an image. In that sense, architecture today is as much a media practice as a spatial one.

The rendered drawing blurs the line between the drawing and the image. It uses a scaled drawing as a base to represent both actual dimensions and spatial experiences simultaneously in one image.

The moving image is more immersive than the photograph offering the ability to look around work in time. In the video the user does not control the camera but technological including virtual reality allow users to control the movement of the camera through a project. Often first planned as a storyboard or montage, the moving image often begins in still life.

The fly-through is often done at the end of construction to document built work at time of completion. The digital fly-through communicates the same information but is usually a rendered product.

A Composite image utilizes multiple types of perspective and projections to create a single image that can communicate experiential and measured information. Composite images borrow both from drawing and image making conventions.

A time-based representation of built work, the Time Lapse may be taken from real life or simulated digitally. Most commonly the Time Lapse aims to show how built work is experienced over long durations to show interactions with light, construction processes, or building traffic.

Collage images join various cut-outs and patterns to make experiential depictions of space and materials. Digital or hand-made, the collage can act as a tool for early exploration, or even as final depictions of work.

Animations is a movement-based technique that can communicate experiences of durations of time, orders of formal operations, or depict serial events in a process. In practice, animations are typically in the form of a GIF

Rendering is a process of developing visual complexity in representations of built work. Photo-real or not, rendering often is utilized to further show opacities, shadows, light emissions, and material interactions. Rendering can be digitally processed or hand drawn. Digital renderings utilize various mapped surfaces, lighting keys, and atmospheric conditions to construct photorealistic views.

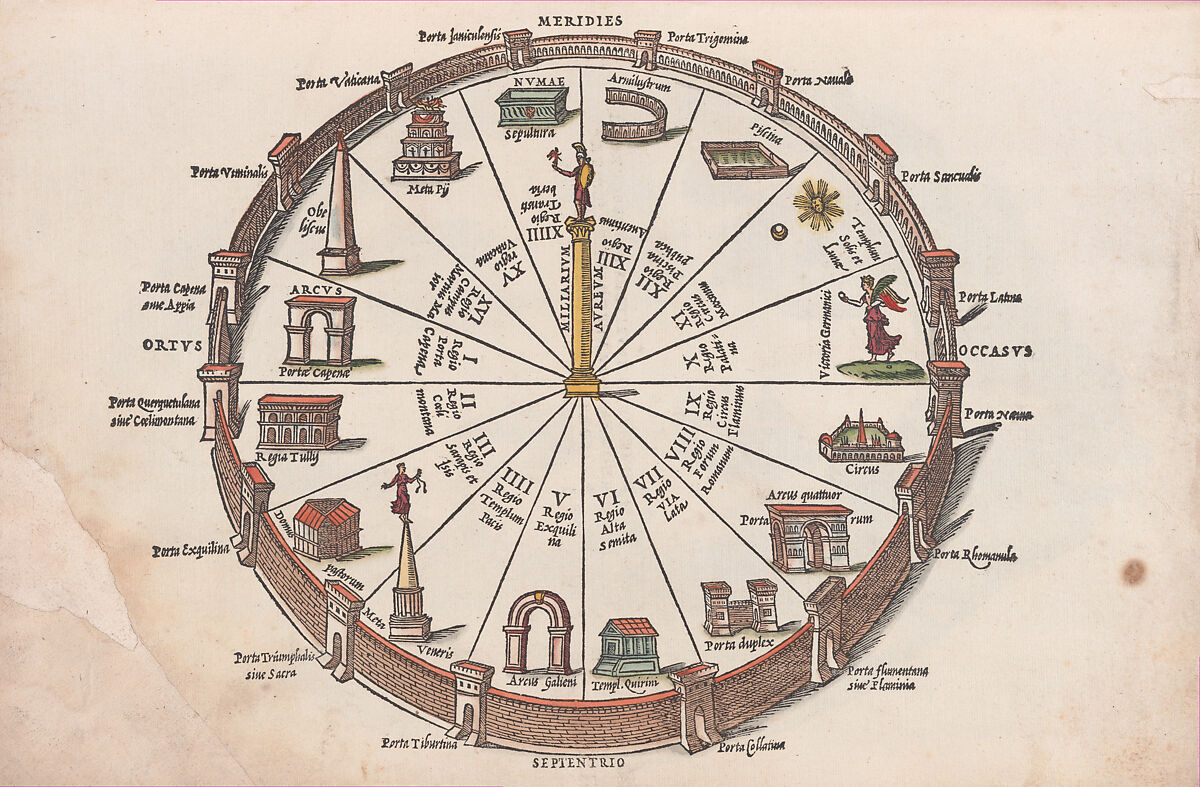

The Diagram is an abstraction of information stored within space. It can communicate formal operations, organizational methods, and building system performance. Most often, the diagram is encountered as a simplified image to quickly relay data. The scope of the diagram can be limited to one room or examine a whole city.

The rendering is a constructed perspectival image, representing spatial qualities of designs. Utilizing measured or unmeasured perspective views, renderings aim to reflect a view similar to how we may experience the project when built. Not limited to photo-realistic representations, the rendering seeks advanced communication of space through the emphasis on ‘look and feel’.

The photograph is the most common image used to communicate built work. The photograph documents physical spatial qualities, and uses multiple types of perspective, lens depths, and lighting to construct views.

Clavo, Mario Fabio. “Map of Ancient Rome.” In Antiquae Urbis Romae Cum Regionibus Simulacrum. Rome: The MET, 1532.

Ferriss, Hugh. “Perspective, 1924.” In Envisioning Architecture: Drawings from The Museum of Modern Art, edited by Matilda McQuaid and Terence Riley, 52. New York: MoMA, 2002.

Ancient Sumerian and Egyptian carved stone tablets show diagrammatic building plans which were created after the building to explain its use. In The Ten Books of Architecture by Vitruvius, the oldest surviving copies from the middle ages included rendered architectural drawings in both plan and elevation along with diagrams to explain proportional systems of orders.

Early Rennaisance builders used renderings to communicate their design ideas, but it was not until mathematical perspective that renderings became typical architectural imagery.

The invention of the camera quickly leads to an explosion of its use for documenting architecture.

The Cornell Box experiments blur the lines between computer rendering and photography. Meanwhile, the diagram obsessed SuperDutch become a dominant force in global architecture.

The rise of Instagram increases the demand and audience for architectural images, mainly photographs. New rendering software and digital tools allow the moving image to emerge through animations and immersive virtual reality.

The categorization of images has greatly changed through serial advancements in digital data processing and computation, resulting in a new approach to information aesthetics in architectural image-making. From 1960 to 1980, early developments of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and digital simulation began to define a shift in image-making, turning to digital tools and territories. Following the release of the first commercial CAD programs in the late 1970s, the digital presence within the profession grew—the computer was no longer relegated to business or science professions; it was a new medium of image-making.¹ Through the adoption of the computer, architects were exposed to fluid exchanges of information and perhaps, conditioned by these exchanges to expect serialized complex outputs. As our digital territories continue to expand, our choices in what data we can represent multiply, and as a result, the line between abstract and technical images continues to blur. John May observes our attitude towards these blurred categories, “casually referring to them as drawings, or photographs, or diagrams, or renderings, often exchanging those names without care,”² implying our digital bias allows us to compound multiple types into single images; information is no longer bound to singular representations. To cope with this, we have turned to the diagram as a multiplier to images, able to continuously adapt and reflect changing inputs.

Our turn to the informative image is the next step in what May describes as "post-orthography"—images are no longer solely static analog representations of buildings as we expect them to appear when built; they are dynamic representations of information, abstracting perceivable and invisible data. We see the hybridized emerge in contemporary practice, looking at studios like MOS, whose signature image is the “screenshot”—a semi-rendered building within software, often accompanied by notation lines with an xyz positioning. This looseness between boundaries of image types reflects our struggle between levels of resolution, resulting in today’s "over-informed" images. Able to represent the physical and metaphysical, architects still need to fine-tune levels of resolution for the sake of effective visual communications. Our ability to view a building elevation as a heat map of light coverage, or a plan as circulatory arrows, suggests layers of diagramming as our primary tactic to disseminate these multitudes. The diagram is our instrument to abstract rich data into low-resolution visuals, allowing us to overlay and read datasets easily. Stan Allen asserts the diagrammatic approach to confront dissolving boundaries: “A Diagrammatic practice… locates itself between the actual and the virtual, and foregrounds [architecture],” the diagram can bridge digital and physical interests, effectively “architecture’s best means to engage the complexity of the real.”³

The diagram allows us to better navigate the porous boundary between image-types as computational advancements allow images to carry more complexity.

As we use them now, images are data-rich visualizations, operating between the experiential and the technical, with new media tools allowing us to continuously encrypt data within images. We can now layer animation, simulation, and representation as a means to explore and reiterate designs thanks to our digital toolset. As digital production becomes our standard mode of operation, we must begin to take critical stances on how we allow the digital to command our images, making sure to intervene with human-defined priorities. As universities continue to expand coursework to scripting, web-based territories, and simulation, there will certainly continue to be a bottom-up ripple in representational traditions, anticipating further “over-informed” images. Repositioning Robin Evans—if architects make drawings of buildings⁴, in a post-orthogonal, post-digital profession, it's possible now that architects make images of information of buildings.

Works Cited

Allen, Matthew, et al. “Screenshot Aesthetic.” MOS: Selected Works, Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

Allen, Matthew. “Representing Computer-Aided Design: Screenshots and the Interactive Computer circa 1960.” Perspectives on Science, vol. 24, no. 6, 2016.

Allen, Stan. “Diagrams Matter.” ANY: Architecture New York, no. 23, 1998. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41856094

Evans, Robin. Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays. MIT Press, 1997.

May, John. “Everything Is Already an Image.” Log, June 2017.

May, John. Signal. Image. Architecture. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019.

Over the last two decades, architectural representation has leaned hard into realism. Renderings today don’t just suggest a building—they stage it. Trees sway, people smile, and golden-hour light floods perfect interiors. It’s not design anymore; it’s performance. And while these images can be stunning, they’re also setting traps.

The main issue? Expectations. Clients see a rendering and assume that’s what they’ll get, down to the last ray of sunlight. But architecture is messy. Budgets shift, materials change, and site conditions push back. The final building rarely matches the image, and that gap between simulation and reality can erode trust.

There’s also a deeper problem. Space becomes secondary to surface when everything looks “real” from the start. We’re designing for the camera, not the body. You start picking textures that render well, or forms that cast nice shadows, rather than thinking through how a space breathes, how it’s used. The seductive power of the image begins to drive the design.

Worse still, many of these images are built from the same libraries, same trees, same furniture, same cool lifestyle flourishes. The result is a weird visual monoculture. A city in Norway starts to look like one in Korea or Brazil. Context, climate, and culture get blurred out in favor of a globally legible aesthetic. Instead of provoking architectural debate, the image smooths over friction and hides contradictions.

The tools themselves aren’t the enemy, but our relationship with them needs rethinking. We need to reintroduce doubt, ambiguity, and even error into the process. Not every project needs to be sold like a luxury product. There’s value in representation that invites questions instead of answering them too neatly. A drawing can lie, too, but at least it leaves something open. A perfect rendering, ironically, closes things off. And that’s where imagination starts to suffer.

Works Cited

Architecture is not a building. Any buildings or artifacts created by architects are, strictly speaking, a product of the manufacturer or contractor. They are more like a secondary outcome of what architects actually produce, an idea and knowledge with data they perceived. Instead, there are representative mediums that architects use in order to convince laymen, scholars, and stakeholders such as text, scaled models, and images. From mind to paper, nowaday on-screen and on virtual platforms, our profession exists on the representation canvas, communicating and influencing society culturally. Among the tools, the use of discursive images has been an efficient tool to enlarge architectural practice by generating discussion on ideas, aligning the culture to the current, and formalizing the principles and theories of space. Recently, with the overflow of data and knowledge from computing and the world wide web, the process faces the change from distribution of architect’s knowledge and immigration of other professional fields. Moreover, the detachment of the image produced and the creator accelerates the phenomenon. We are at the hinge point in the middle of the digital era where changes and transitions occur every second and struggle with finding architects’ immanent value of image products. To recover our value, the architect needs to start by adapting the immersive technologies and reclaim the new form of a discursive image as a product of the profession. The puristic form of spatial ideas and cultural ideology of architectural perspective must be reclaimed in the digital world by competing against or collaborating with non-architectural creators otherwise, presumably architectural profession would no longer exist in the current structural system. Architects with no built project would be possibly considered as other digital creators if we cannot refind ourselves the distinctive value of the product of practice in architecture. Would this emergence of immersive technologies be a threat to our profession or be a precursor to enlarging our field of practice? How would architectural discursive images transform from static images?

Works Cited

Architecture theorists have championed the social value of the architect through the understanding and application of drawing principles, moving images from the mind to paper, and mapping the right parts together into a building. Our profession exists on paper and in theory against contending with craftsmen and engineers in the built form. The discursive image has been a unique tool in the architect’s arsenal for theorizing space to push practice in alignment with current culture or generate discussion on where architecture can force the culture to align.

This process has been unchanged up until recently. The digital hinge point around computing and knowledge sharing via the world wide web has distributed the architect’s tools to the layman. Today, the profession struggles with finding itself in society as our most prominent tools of shaping our discipline have become cluttered with non-architectural creators—both conscious and artificial—and collective action in the assemblage of these images.

These images have become an architecture to the public, and our societal value has decreased as non-architecturally produced imagery has dominated the discourse on ‘ugly’ buildings. To recapture our worth, the architect needs to reclaim the discursive image as a product of the profession or curate non-discipline images into a new narrative of the image as a tool to produce cultural ideas—and not architecture as the image only.

Works Cited

For this assignment, our goal was to look at the power dynamics that images represent in relation to the products of practice within architecture. The agendas we explored with this research were looking at the image as propaganda, revealing how the image is used to display power, and finding through the image how images convey the autonomy of power. Ultimately this agenda led us to question who we as architects make architecture for and begin tracing that power through the image. This research was meant to accumulate an overall understanding of what is missing in the architecture cannon—resulting in how the image can be used to expand and subvert the cannon. At the beginning of this research, my interest was focused on the social implications of image and how architecture in the past communicated our value to the public through the role of image. I believe that the discipline and the profession can rely more on the hybridized image to be more impactful and engaging with the real world. The role of the image throughout the history of architecture is typically the thing that archived and carried the profession. Yet, the image typically only told the story of the elite or those in power. By rethinking image and how we display the image of architecture to the world, is it possible for the architectural image to engage more in social, political, and, simply put, the real issues that impact our world? Can the image separate from only those in power and speak more inclusively? Through engaging in a discourse focused on the image, is it possible to rethink and reshape the practice of architecture and societal views of architecture?

Works Cited

Chalk, et al. Archigram: the Book. Circa Press, 2018.

Tafuri, Manfredo. Architecture and Utopia: Design and Capitalist Development. MIT Press, 1976.

Société des architectes diplômés par le gouvernement. Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité: Bulletin De La Société Des Architectes Diplômés Par Le Gouvernement., 1967.

Vidler, Anthony., and Claude Nicolas Ledoux. Claude-Nicolas Ledoux: Architecture and Utopia in the Era of the French Revolution. Birkhäuser, 2006.

Rowe, Colin, and Fred Koetter. Collage City. MIT Press, 1978.

Allen, Stan. “Diagrams Matter.” ANY: Architecture New York, no. 23, 1998. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41856094

May, John. “Everything Is Already an Image.” Log, June 2017.

Morris, Roderick Conway. “If a City Were Perfect, What Would It Look Like?” The New York Times, The New York Times, 8 May 2012.

Lavin, Sylvia. Kissing Architecture. Course Book ed., Princeton University Press, 2011.

Gramazio, Fabio, et al. Konrad Wachsmann and the Grapevine Structure. Park Books, 2018.

Wigley, Mark, et al. Konrad Wachsmann's Television: Post-Architectural Transmissions. Sternberg Press, 2020.

Moos, Stanislaus von, and Le Corbusier. Le Corbusier, Elements of a Synthesis. MIT Press, 1979.

Malevich, Kazimir Severinovich, et al. Malevich. Tate Publishing, 2014.

Hays, K. Michael. Oppositions Reader: Selected Readings from a Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture, 1973-1984. Princeton Architectural Press, 1998.

Allen, Stanley, and G. B. Piranesi. “Piranesi's ‘Campo Marzio’: An Experimental Design.” Assemblage, no. 10, 1989, pp. 71–109. JSTOR.

Allen, Matthew. “Representing Computer-Aided Design: Screenshots and the Interactive Computer circa 1960.” Perspectives on Science, vol. 24, no. 6, 2016.

Allen, Matthew, et al. “Screenshot Aesthetic.” MOS: Selected Works, Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

May, John. Signal. Image. Architecture. Columbia Books on Architecture and the City, 2019.

Rossi, Aldo, and Peter Eisenman. The Architecture of the City. MIT Press, 1982.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. “The Barest Form in Which Architecture Can Exist: Some Notes on Ludwig Hilberseimer’s Proposal for the Chicago Tribune Building.” The City as a Project, 31 Oct. 2011, thecityasaproject.org/2011/10/the-barest-form-in-which-architecture-can-exist-some-notes-on-ludwig-

William O. Gardner. The Metabolist Imagination. University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Kahn, Louis I., et al. The Travel Sketches of Louis I. Kahn: an Exhibition. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 1978.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Prism Key Press, 2010.

Sarkis, Hashim, et al. The World as an Architectural Project. The MIT Press, 2019.

Forty, Adrian. Words and Buildings: a Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 2000.