Buildings are a direct product of architectural practice when architects expand their contemporary agency—taking on roles like developer or builder—to better align the final outcome with their original design intent. While architectural practice today is most commonly defined by its separation from manual labor and the building trades via the creation of “instructions” or architectural drawings and images, architects have long engaged directly in the making of things—designing and fabricating furniture, objects, interiors, and entire structures. Across scales, the act of building is a reconsidered product of practice when architects take on new expanded roles in the design process: shaping outcomes not just through drawings, but through material decisions, construction methods, and project delivery models that bring design and execution closer together.

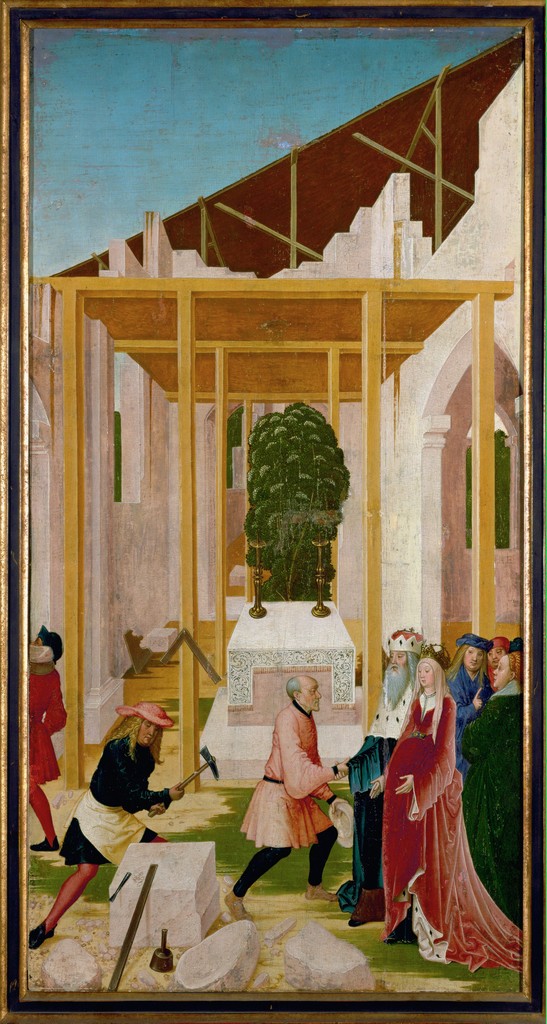

Since the earliest acts of building, the person in charge of its design was synonymous with its actualization. However, in the Renaissance, the profession of architecture slowly emerged as a high art, distinctly engaged with building only through the abstractive tools of drawings and models in order to create a series of instructions, divergent from the master builder known previously1. Amid the effects of industrialization and a growing disconnection between architects and the act of building2, the profession saw a return towards construction as an essential part of architectural authorship. This renewed interest in building craft reflects a desire to reestablish a tighter link between design intent and final product—one that recalls the role of the master builder. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin School positioned hands-on construction as foundational to architectural understanding, but this approach has extended far beyond the academic setting3.

In practice, architects like Charles and Ray Eames took on the assembly of their own home, working directly with materials and prefabricated parts4, while figures such as Alvar Aalto and Eileen Gray blurred the boundaries between architecture, furniture, and industrial design. These efforts exemplify a broader shift in professional practice—where designing, fabricating, and building are increasingly seen as interconnected parts of a single architectural process, defined by an expanded role of the architect earlier in the design process.

Today, architectural practice is increasingly defined by expanded roles that go beyond design alone. In design–build models, architects assume the role of contractor, integrating construction management into their scope. In design–develop models, they go further still—acting as owners and financiers of their projects. Both frameworks represent a redefinition of practice that gives the architect greater agency over outcomes by collapsing traditional divisions between disciplines. In each, the architect takes on a series of assurances—commitments to cost, design quality, timeline, and legal accountability—designed to close the persistent gap between design intent and built reality.

In the Design Development model, the whole process of development beginning from financing all the way to construction is managed within a single entity. Such entities can be led by a developer with an in-house architect, or an architect with the endeavors of acquiring agency over building.

Most Structures from the earliest human settlements are self built structures before the advent of the profession of the Master Builder.

The Design Build model for project delivery puts the design and construction teams under one roof. Often run by a general contractor or an architect, this format is especially popular due to the lack of liability gap between the architect and builder.

A physical structure of any size that is produced through the design & planning process of an architect. As the end goal of the architect’s work, these vary in scale and purpose ranging from small objects to large complex structures. Although every building is seemingly a product of the architect, the contract of a modern architect terminates with a set of drawings and specifications which serve as instructions for a third party - the builder - to assume responsibility for the construction process. This division of labor effectively disassociates the building from being the immediate product of the architect’s work. Accordingly, as the ‘building’ as a product has been contingent upon the evolving boundaries of architectural practice, the classification of ‘buildings’ in this category is framed through the evolution of profession that allowed the building to be a direct product of the architect.

The Design-Bid-Build model is a traditional and widely used project delivery method that restricts the scope of architect’s work only to design and planning.

Throughout human history, most buildings have been self-built by their inhabitants. However, when larger structures of civic importance were developed in ancient cities, construction was managed by a master builder.

While the guild system flourished in Europe, master masons traveled throughout regions, oftentimes moving from project to project before completion and taking up work started by others as funding became available.

The master mason begins to separate from the Renaissance Architect, an intellectual role distinct from labor which becomes formalized in this period.

The role of the architect becomes fully separated from labor. Builders rely on drawings and on-site instruction from the architect. The rise of literacy and standardized mass production allows further separation of the architect and builders.

Architects and builders become recoupled under a single corporate umbrella of the design-build structure. Most of these companies are builder-led rather than architect-led, although both exist.

John Portman innovates the design-develop structure for building. The architect secures funding and proposes a project. Most firms in this category are developer-led rather than architect-led.

There is an explosion of design-build construction in the United States. The lack of liability gap between architect and builder makes this an attractive option for public projects and currently holds a large and growing market share.

Architect-led-build reframes architectural practice around the concept of assurance: the ability to guarantee outcomes across cost, design integrity, delivery, and legal responsibility. In contrast to traditional design-bid-build models, where risk is offloaded and responsibility fragmented, architect-led-build centralizes control. By collapsing the distinction between designer and builder, architects design but also manage and deliver the project, reclaiming agency over the full arc of building production.

The richest solutions arrive when architects are responsible for all components of project delivery, from concept to construction. “Building” as a product of practice moves away from purely cultural or intellectual projects under the traditional role of practice in project delivery. In the design-build scenario, project delivery is a managerial project, where “assurances” have a new and different meaning, no longer offloaded under the assumption of risk and legality. Here, control of the construction phase as “creative contractors” means the design assurance, cost assurance, legal assurance, and delivery assurances are withheld by the architect, no longer afraid of the presumption of risk associated with each. As risk is embraced in the design-build scenario, so is agency over the outcome of each component: the assurance that intent and outcome are singular in effect/nature.

This model offers cost assurance through early integration of design with constructability and budgeting, eliminating inefficiencies introduced during bidding. Design assurance is preserved by avoiding the traditional handoff to contractors who may not recognize the tolerances or nuances essential to architectural intent. By retaining authority over construction, architects ensure that the built product remains faithful to its conceptual origin. Timeline assurance is embedded through seamless coordination, with feasibility tested early and delivery managed proactively rather than reactively. In assuming these roles, architects take on legal assurance as well, embracing the liability traditionally deflected to contractors. But with that risk comes the ability to manage it: transforming the architect into a “creative general contractor” who understands construction logistics, oversees subcontractors, and delivers a coherent, accountable process.

Building, as a product-of-practice, is a determinant of risk and control. In both the developmental and construction schemes, architects take on new and additional roles, reminiscent of the master-builder's all-encompassing know-how, in order to control and manage risk associated with cost, design, legal responsibility, and timeline delivery. Acceptance of risk requires construction and management expertise in the components of detail, manufacturability, technology, and market. These new roles extend beyond the architect's former and diminished capacity as singularly a cultural producer who guides, but does not control, the construction and developmental processes. Building (as a product of practice) under the normal and traditional role of the architect requires periods of “hand-off” or risk offloading between the client and contractor in a three-way relationship. When the architect absorbs the role of the client (as a developer), or the contractor (as a builder), the building product has a purportedly closer relationship to the conceptual beginnings of the project. The “pureness” of design intent is supposedly left intact when design goals are not mediated through non-architectural parties.

I might question this claim—that pureness of design intent, now categorized by its “assurance,” is always a mediated project, that the identity of the labored party does not change the role that the labor has on the intellectual and cultural project of architecture. Design intent will always be mediated from origination to construction. Architect-led-build is not necessarily a return to self-building, but instead I might consider it a forward-looking model where the architect ensures the integrity of every phase. It restores architecture’s capacity to lead, not just creatively, but operationally, by grounding authorship in responsibility. Single-source responsibility produces “assurance” of building as a product itself.

Works Cited

Since the Renaissance, architects have aimed to preserve their professional autonomy by separating the intellectual work of design from the labor of construction. This shift formalized the architect’s role and paralleled increasing complexity in building functions, leading to the specialization of design and construction professions. Consequently, architects assumed a more narrowly defined role focused on design within a broader service framework, historically shaped by the needs of patrons—as history illustrates: there would have been no Parthenon without Pericles, and no Versailles without Louis XIV.

This essay argues that the architect’s role has been shaped fundamentally by supply and demand dynamics. To explore this, it examines three architect-developers—John Portman, Jonathan Segal, and Jonathan Tate—each practicing within distinct economic contexts in the United States.

John Portman is widely regarded as the pioneer of the architect-as-developer model in American architecture. His practice bridged the financial demands of real estate development with the creative aspirations of design. Motivated by a desire for creative autonomy, Portman moved into development to gain control over the entire process—from concept to execution. His rise aligned with the post-WWII era of urban renewal (1950s–1980s), particularly in Sun Belt cities like Atlanta, where municipalities sought private investment to redevelop downtowns. Portman’s Peachtree Center began as a single hotel and expanded into a large-scale complex, driven by Atlanta’s economic growth and the public-private development climate. His success was rooted not just in personal vision, but in his ability to align that vision with the larger economic and urban renewal strategies of the time.

By the late 1990s, a different model emerged. Jonathan Segal, based in San Diego, exemplified a localized, self-reliant version of the architect-developer. Segal launched his practice during the 1989 recession and the savings and loan crisis, capitalizing on low land costs and minimal competition. His focus on small- to medium-scale multi-family housing in dense urban environments responded to rising demand for urban living, environmentally conscious design, and favorable lending conditions in the 1990s. By controlling all stages of development and financing his own projects, Segal reduced costs and preserved architectural quality. This independence also protected him during the 2008 financial crisis, when speculative developers faltered. His model illustrates how economic downturns can inspire leaner, more adaptable architectural practices.

Jonathan Tate represents the post-2008 generation of architect-developers. Starting his New Orleans-based practice amid a challenging economic environment, he responded to limited professional opportunities by taking on development roles himself. Tate focused on adaptive reuse and urban infill, strategies that minimize financial risk and environmental impact while revitalizing neglected neighborhoods. His projects, such as the Starter Home series, offered middle-income housing options at a time when affordability and sustainability had become urban priorities. The St. Roch Market project further demonstrated his interest in community-oriented, mixed-use development.

Tate’s work was also marked by innovation in project financing. In 2019, he led the first real estate equity crowdfunding initiative in the U.S., raising $95,000 through the Small Change platform to build two homes in New Orleans’ Milan neighborhood. This approach allowed him to bypass traditional financial institutions and speculative risk, demonstrating a flexible and resilient model for emerging architects.

In conclusion, the practices of Portman, Segal, and Tate show how architects can reclaim agency by adapting to shifting economic landscapes. Each responded to both the demands and constraints of their respective eras—urban renewal, post-recession recovery, or post-crisis resilience—by evolving into the architect-developer role. These case studies highlight how economic conditions not only influence architectural output but also foster innovative models of practice that merge creative control with financial sustainability. As such, the architect-developer stands as a viable career pathway for future architects in an ever-changing urban economy.

Works Cited

Historically, dated back from early civilization to medieval times, the cities were once developed by master builders of craftsman and builders from different trades. During that period, the master builders are recognized by their ability to design the buildings, but also to think about the structure, tectonics, and construction methods. We can understand the builders as a precursor to the architect, engineer, and construction manager of modern times. The builders weave together their knowledge and skills to the development of the building from beginning to the end.

During the Renaissance period, there is a growing desire by the architects to separate themselves from trades. There is also the desire by the architects to pursue art and culture. The differences in approaches resulted in a separation between thinking and the execution of a building. For example, when Fillippo Brunelleschi designed the Florence Cathedral, he created the hoisting machines to lift up heavy materials. His invention improved the construction process. In order to come up with solutions to construct masonry dome, he studied the domes of Pantheon in Rome, where single-shell dome were supported with structural centering. He designed the double-shell structure with hollows between the layers, and tension rings nested inside. The structure, reduce the weight of the dome, and the cost in material and labour. In comparison, Leon Battista Alberti, the architect during the same period inspired artistic practices and theoretical thinking. His research on the classical forms has not only revived the building, but also bring up the discussion toward architectural antiquity and aesthetic theory.

During the industrial revolution, the role of architect, engineer, and builder are further separated. There was a need for specialization of role, such as the technical expertise for industrial buildings. In addition, there was also a need for efficiency and quantity over quality due to the demands of the economy. The design-bid-build approach emerged where owners choose the design from the architects and bid out the low-cost construction team.

As described earlier, the design build approach is rooted in historical practices. It is an approach that provides a single source for the entire project, allowing the overlaps between design and construction phases. The architects are responsible for the entire project through construction phases. The single point of responsibility allows room for adaptations during the construction process. More importantly, the method helps to enhance the aesthetics appeal, and quality control of the project.

However, the current mode of architectural practices rely mostly on Design-Bid-Build approach, where there is a separation between architects and contractor. The architects do not have further obligation after the drawing set is submitted. In this approach, the owner is responsible to communicate with the designer and contractor. The gap between architects and contractor produces potential issues, such as quality and material cost. Furthermore, there is a liability issue in this approach, since there is a lack of agreement between architect and constructor. In other words, it is possible for the two to blame each other, when there are problems come up.

During the recent days, we can start to see a come-back in design build approach. There is a growing interest for the architects to convey the design and to have more integration in construction. Gluck +, formally Peter Gluck and Partners Architects, is a New York based firm known for architect led design build practices. The approach provide a single-source responsibility for an entire building project, for design to construction to commission. The architects in the firm are also construction managers, meaning there are fluid communication between design and construction. The founder of the firm Peter L. Gluck received his Masters in Architecture at Yale School of Architecture. He was influence by the design-build culture in Yale, where direct experience is valued over drafting on papers. Throughout his studies and his early career, Gluck has shown interests in building his own designs. In the late 1980s, Gluck designed the addition of a residence by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in Connecticut. His design follows the styles of Mies, yet also incorporates some new elements. Due to the project’s technical challenges, Gluck worked closely with the contractor, and in the end taking the role as a contractor. Throughout the project, the team spent a lot of time on site, but they was not compensated nor having the authority to make directions to the subcontractors. The experience pushed Gluck to rethink about delivery method and later pursued the architect led design build approach.

Aside from quality control, there are also other benefits of design build approach. Architects’s sensitivities in material and cost will support issues during construction. Gluck’s recent work ‘the Stack’, for instance, has successfully solve the problem of small urban site through having modular pre-fabrication construction. The off-site construction is not only an alternate method in urban sites, but also is a solution for accelerated schedule and shorter financing period. In this project, both quality and economy are ensured.

Works Cited

Allen, Stan. “Field Conditions.” Essay. In Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2012.

Forest Service, L. W. Smith, and L. W. Wood, History of Yard Lumber Size Standards § (1964).

Richard, Roger-Bruno. (2005). Industrialised building systems: Reproduction before automation and robotics. Automation in Construction. 14. 442-451. 10.1016/j.autcon.2004.09.009.

Sullivan, Barry James. Industrialization in the Building Industry. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1980.

Curtis, Oliver J. “Nominal Versus Actual: A History of the 2x4.” Harvard Design Magazine, no. 45 (2018).

Carpo, Mario. “Particlised: Computational Discretism, or The Rise of the Digital Discrete.” Architectural Design 89, no. 2 (2019): 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/ad.2416.

Kieran, Stephen, and James Timberlake. Refabricating Architecture: How Manufacturing Methodologies are Poised to Transform Building Construction. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

Robotic Building: Architecture in the Age of Automation (Detail Magazine)

Sharples, Coren D. “Technology and Labor.” Essay. In Building (in) the Future: Recasting Labor in Architecture, edited by Peggy Deamer and Phillip G Bernstein, 90–99. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010.

Carpo, Mario. The Alphabet and the Algorithm. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Seelow, Atli M. 2018. "The Construction Kit and the Assembly Line—Walter Gropius’ Concepts for Rationalizing Architecture" Arts 7, no. 4: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040095

Herbert, Gilbert. The Dream of the Factory-Made House: Walter Gropius and Konrad Wachsmann. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1986.

Pye, David. The Nature and Art of Workmanship: Cambridge: University Press, 1968.

Banham, Reyner. “The New Brutalism.” Architectural Record, December 1955.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility.” Essay. In The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. London: The Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2008.

Le Corbusier. Towards a New Architecture. Brewer, Warren & Putnam, 2014.

Epstein Jones, Dora. “Walter Gropius and the (Not So) Infinite Possibilities of Prefabrication.” arcCA Digest 7, no. 4 (2007).