Codes, existing in dynamic forms, have been fundamental products of architectural practice since antiquity. The design of Greek temples, which was not planned in advance but instead evolved from a blend of previous templates and new alterations, became a code of practice in itself1. Architecture, then, practiced by master builders, was not so much the design of a novel thing but a result of careful steps where the code was physically embedded in the process2. Throughout the Renaissance and modernity, codes have played a significant role in how architects have shaped their own understanding of the world, attempting to codify through quantitative and rational metrics. Palladian proportion3, Nuefert's standards4, and Corbusier's modulor5 are all codes produced by the architects. More pervasively, drawing standards that we take for granted today, such as line weights and hatches, are products of architecture practice to communicate both within and outside the disciplines.

Yet, it is also an inevitable fact that codes introduced from non-architectural disciplines have shaped architecture (even though such codes would not exist without architecture). In antiquity, the Code of Hammurabi stated the responsibility of builders for construction safety6. Standard units of materials defined by code, such as bricks and tatami-mat, introduced specific grid systems in architecture. Zoning and building codes have produced specific typologies; a series of Building Acts7 in the late 19th-century London contributed to its unique terraced housing typology, and with a more recent example, Podium construction (or 5-over-2 construction) has become a popular mixed building type impacted by the IBC section 510.28. However, this power dynamic of who writes code for whom keeps evolving. Some of these codes implemented by other disciplines are now rewritten by architects, expanding the agency of architecture practices.

Codes are at the core of architectural practice, and today, they exist at the crux of an inflection moment in what we produce, deeply related to the question of architects’ agency in the society ahead.

Languages that evolved naturally in humans through use are considered natural languages. They are the unplanned result of the desire to communicate. Used in conjunction with drawing and graphic standards, it remains one of the most effective ways architects communicate their ideas.

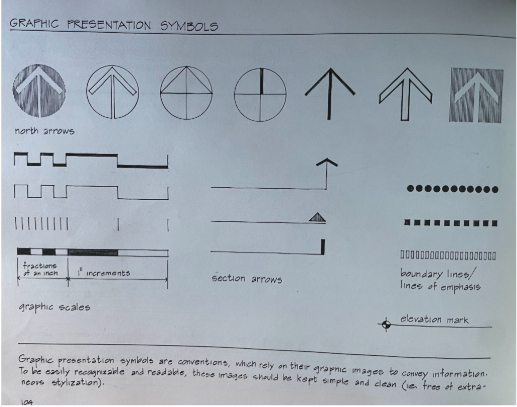

A technical standard is a formal document which establish uniformity from the field. These include units of measurements, standard details means and methods. Technical standards are aimed at trades and material performances. Specifications are a way for architects to communicate and reiterate technical standards to builders. The most common technical standard for architects are graphic standards which allow drawings to be read and interpreted. Line weights, line styles and symbols, form a visual coded language.

A proportional system, uses memorized or written ratios to solve geometric problems related to construction. Used throughout the ancient world espeically among Greeks, proportional systems provided divine instructions before the advent of the architect.

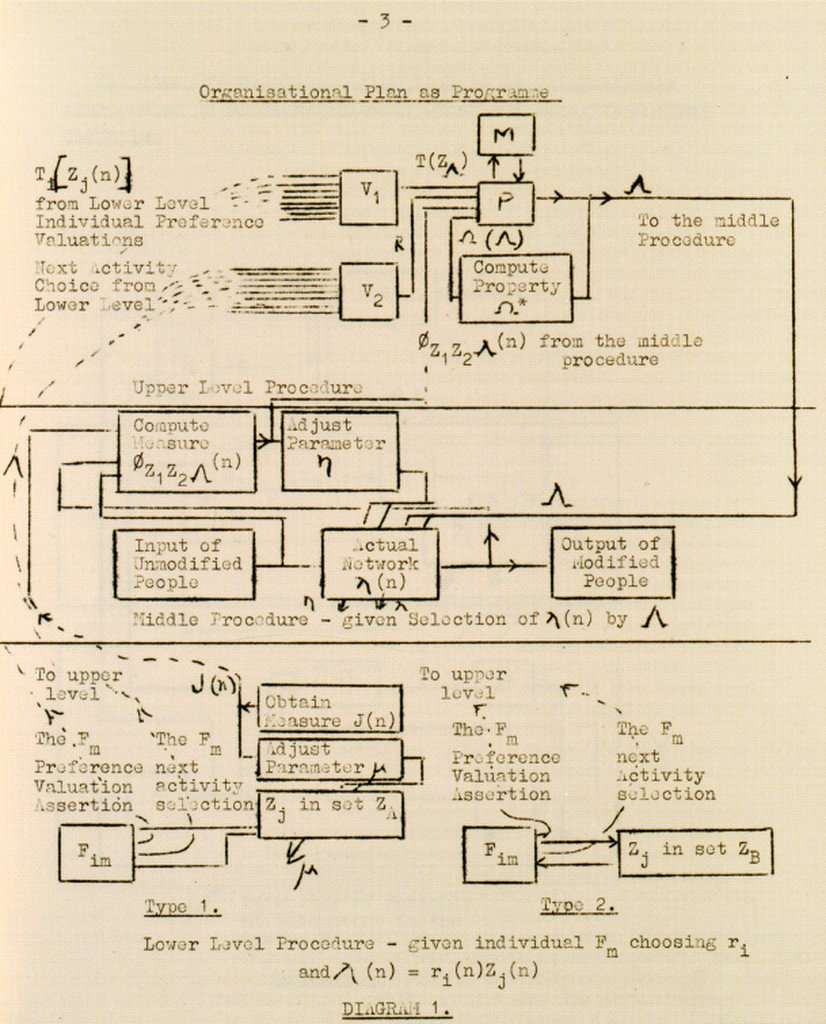

Value tables, flow charts, and computer code are assemblies of information that can be read either by a human or machine user. The rules for understanding the data structure is often not embedded in the data itself and instead relies on past experience or software to decipher the data. Most software uses a proprietary file format and data structure, shared file types across platforms allows communication between architects and trades.

Graphic standards in architectural drawings are the codified conventions and systems used to communicate spatial ideas and construction information universally. They establish rules for line types, symbols, dimensions, annotations, and layouts, ensuring clarity, consistency, and accuracy across all stages of design and construction.

Design systems are structured methodologies that organize, encode, and represent the relationships, processes, and information essential to architectural design and production. Frameworks such as diagrams, flowcharts, and value tables integrate data from multiple variables to synthesize architectural ideas and approaches to problem-solving. By translating complex “datasets” into comprehensible and actionable forms, architectural design systems enable effective communication across interdisciplinary teams and streamline design workflows throughout the design and construction process.

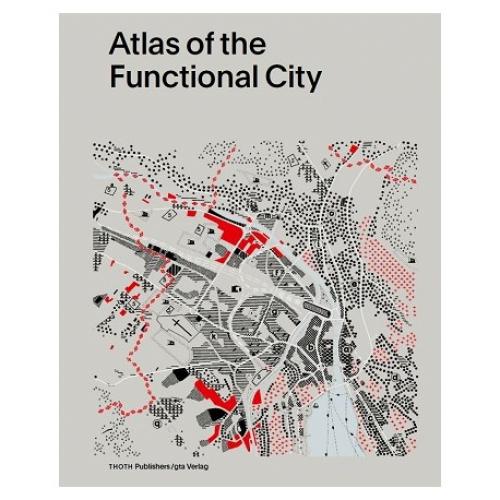

Zoning codes can specify allowed use, building types, styles, height, and floor area ratio (FAR), for the development of a region. Conventionally, urban planners and/or municipal officials write one, and therefore, it was considered to be code from an external discipline that determines the building envelope. However, recently, there have been more cases where architects are actively enrolled in the production of zoning codes.

Building codes are written standards for building that a) state the accountability of architects and builders, and b) ensure the safety and wellness. In the modern formal building code, first implemented for public safety, they have been expanded to ensure a built project meets minimum requirements for accessibility and sustainability.

Malton, James. Front of Trinity College, Dublin. 1793. Aquatint, 20cm x 30cm.

Ching, Francis D. K. “Graphic Presentation Symbols.” In Architectural Graphics, 104, n.d.

Es, Eveline van, Gregor Harbusch, Bruno Maurer, Muriel Perez, Kees Somer, and Daniel Weiss. Atlas of the Functional City, 2014.

C.M. Lee, Christopher. Dominant Types, Honk Kong. 2011. http://thecityasaproject.org/2011/08/type/.

Alexander, Christopher. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York, N.Y.: OUP, 1977.

Ferriss, Hugh. “Evolution of a City Building Under the Zoning Law.” New York Times, March 19, 1922.

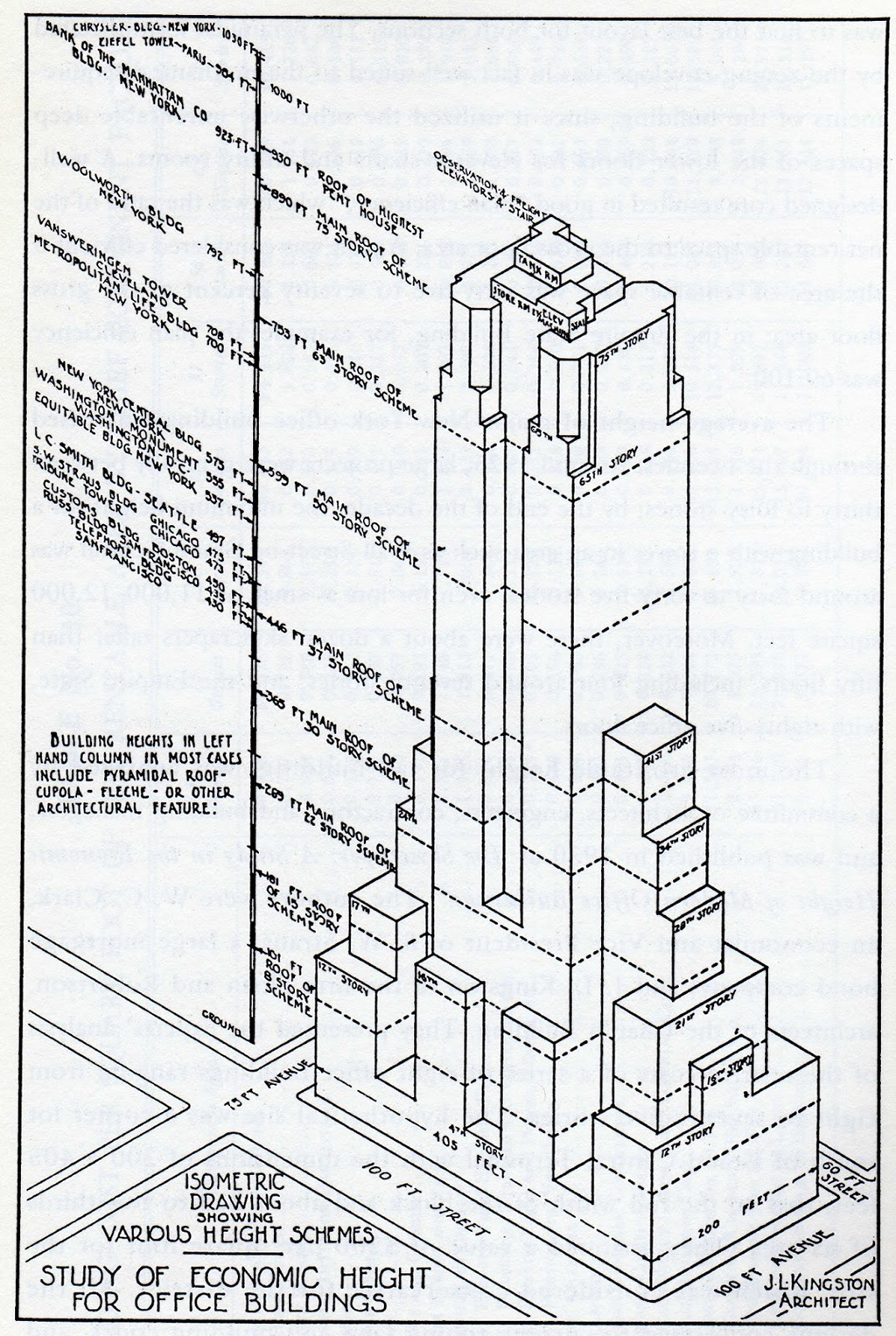

Clark, W. C., and John Lyndhurst Kingston. “Study of Economic Height for Office Buildings.” In The Skyscraper -A Study in the Economic Height of Modern Office Buildings, 15. New York ; Cleveland: American Institute of Steel Construction, inc., 1930. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.169080/page/n7/mode/2up.

Hedman, Richard, and Jr. Fred Bair. In And on the Eighth Day... Philadelphia: Falcon Press, 1961. https://www.planning.org/pas/reports/report165.htm.

Before architects, builders managed the construction and realization of a design through proportions, human body measurements, common language, and building codes that existed in the earliest cities.

Medieval builders used 1:1 mockups to create full-scale details for construction. Master masons memorized proportional systems to aid their design.

King Henry standardized the foot measurement in England. Many builders used metal plaques to show their use of the standard measurement on their buildings.

Urbanization and deadly fires create the need to adopt fire codes for public safety. The French Revolution rejects monarchical systems of measurement and leads to the adoption of the meter across Europe. Industrialization leads to the standardization of building materials.

As industrialization and urbanization increase, fires spur new guidelines for building codes. Additionally, the advent of the skyscraper creates the need for zoning laws in New York City.

As industries become globalized, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is formed. Computer-aided design systems need standardized data structures to communicate.

The Americans with Disabilities Act is passed, ensuring equal access the public buildings. Most architects transition to computer-based drafting, multiple file types, and digital drawings formats become part of the profession.

Open Source Architecture¹ reimagines spatial production as the decoding of latent patterns in urban environments, an engagement with a recursive public, and the re-encoding of static artifacts into dynamic dialogues². This encoding-decoding paradigm extends to architectural drafting practices, where lineweights, hatching patterns, and 2D representations serve as a codified language that simultaneously abstracts and communicates spatial intentions³.

Encoded data such as patterns of occupation and the synergy between neighbourhoods are all latent relationships encoded in physical space. Today, Machine Learning algorithms for feature extraction unveil patterns within our built environment, accelerating the feedback loop between learning tacit knowledge and realization⁴. Like medieval master builders who worked without detailed drawings but with sophisticated systems of proportion and craft knowledge, today's open architecture operates through shared, evolving codes rather than fixed documents⁵.

The contemporary architect, rather than standing as the sole author of built form, might more accurately be understood as a curator of influences, a mediator between multiple knowledge systems, and a facilitator of collaborative processes that extend beyond human participants to include algorithmic agents and material intelligence⁶. This reconfigured understanding of architectural agency does not diminish the architect's importance but situates architectural creation within broader networks of knowledge production that have always characterized the built environment.

Works Cited

Alexander, Christopher. Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Harvard University Press, 1964.

Carpo, Mario. The Second Digital Turn: Design Beyond Intelligence. MIT Press, 2021.

Evans, Robin. Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays. MIT Press, 1997.

Forty, Adrian. Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 2000.

Kelty, Christopher M. Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. Duke University Press, 2008.

Pérez-Gómez, Alberto, and Louise Pelletier. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge. MIT Press, 2000.

Picon, Antoine. The Materiality of Architecture. University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Ratti, Carlo, and Matthew Claudel. Open Source Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Yanagi, Soetsu, and Bernard Leach. The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty. Kodansha USA, 2013.

Whether architects embrace it or not, regulatory codes have long shaped the aesthetics and formal outcomes of architecture. The 1894 London Building Act, which functioned both as a zoning code and a building code, established foundational parameters for today’s terraced house typology—regulating aspects such as rear yard angles and permissible building materials¹. In more recent contexts, the emergence of "podium construction" (commonly referred to as 5-over-2 construction) in the United States reflects a direct response to both the International Building Code and economic viabilities². To varying degrees, architectural imagination is thus constrained—or at least guided—by codes, whether consciously or unconsciously.

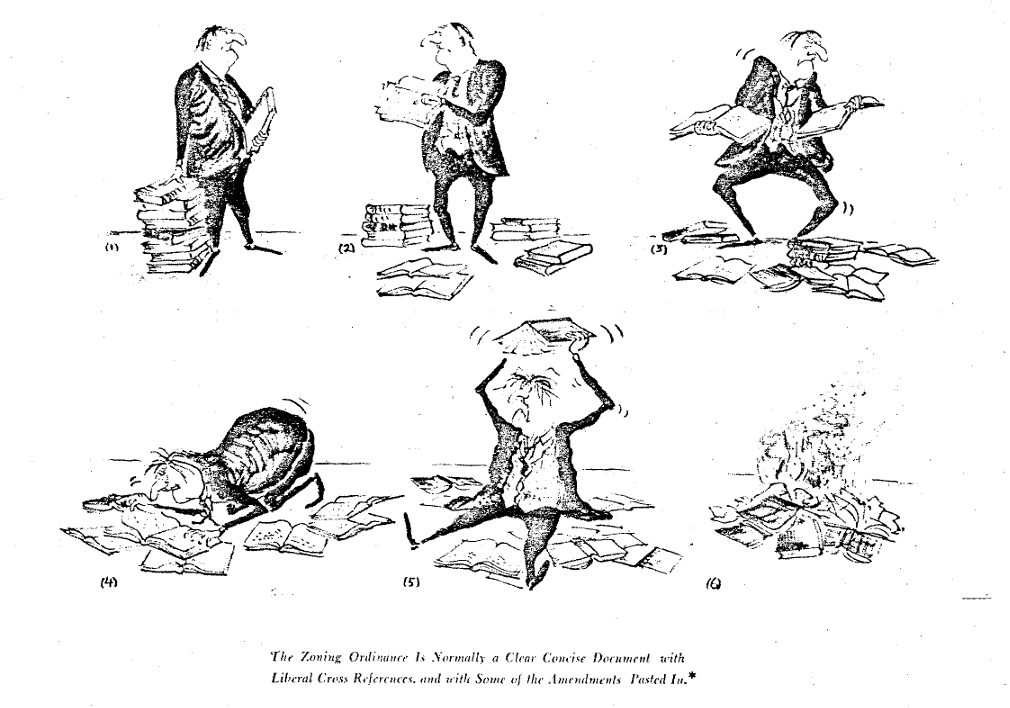

With increasing concerns integrated into building and zoning codes—ranging from safety and accessibility to sustainability and density—the volume and complexity of these regulations have grown to such an extent that it has become nearly impossible for architects to fully digest or proactively engage with them³.

This raises a critical question: Rather than being passive respondents to regulatory frameworks, how might architects reclaim agency in shaping them? How can codes become a product of architectural practice once again?

One potential answer lies in the proposition that architects themselves write codes, utilizing the tools they are most proficient in—visual representation and critical spatial thinking. Inspired by A Pattern Language by Christopher Alexander⁴, architects Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk of the firm DPZ pioneered the first form-based code in the 1980s⁵. A form-based code is defined as “a land development regulation that fosters predictable built results and a high-quality public realm by using physical form as the organizing principle for the code”⁶. Unlike traditional zoning codes—which often focus on abstract and quantitative parameters such as dwelling units per acre, setback distances, and parking minimums—form-based codes prioritize the spatial relationships and physical form of buildings to promote walkability, community character, and urban vitality⁷.

Critically, form-based codes integrate visual documentation, making them inherently more accessible to architects. This visual orientation aligns closely with architectural modes of thought and communication, transforming code from a bureaucratic burden into a tool for design.

This shift in practice introduces a new dynamic of authorship and influence within the architectural profession. Architects who engage in code-writing acquire a distinctive form of agency, as the regulatory frameworks they create shape the design decisions of others working within those parameters. As Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk has noted in a private interview⁸, code-writing should not be understood in binary terms of complete control or total freedom; rather, it involves a gradation of regulatory influence that varies according to the goals and context of each project⁹. Plater-Zyberk also highlights the productive tension between designing architecture and writing codes. She observes that it is intellectually engaging to witness how architects respond creatively to the constraints embedded in the codes she has contributed to¹⁰.

Her reflections underscore the importance of architects’ involvement in code-writing processes, particularly because they possess a deep understanding of how construction methods inform spatial planning and design¹¹. In this way, architects are uniquely positioned to shape codes that are both technically grounded and generative of thoughtful design outcomes.

The form-based code is not merely a representational innovation. By embedding visuality into its framework, it becomes a vibrant and constructive extension of architectural practice. In reimagining the very mode of existence of codes, architects can transform what is currently a site of constraint into a site of opportunity and agency.

Works Cited

Alexander, Christopher. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Bsummers. “What Is New Urbanism?” Congress for the New Urbanism, May 18, 2015. https://www.cnu.org/resources/what-new-urbanism

Ching, Francis D. K. Building Codes Illustrated: A Guide to Understanding the 2012 International Building Code. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2012.

Form-Based Codes Institute at Smart Growth America. “Form Based Codes Archives.” Accessed May 12, 2025. https://formbasedcodes.org/tag/form-based-codes/

DPZ | CODESIGN. “Form-Based Codes Archives.” Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.dpz.com/project_category/form-based-codes/

Malone, Terry. “5-over-2 Podium Design.” Structure Magazine, January 2017. https://www.structuremag.org/article/5-over-2-podium-design/

Parolek, Daniel G. Form-Based Codes: A Guide for Planners, Urban Designers, Municipalities, and Developers. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008.

Malone, Terry. “5-over-2 Podium Design.” Structure Magazine, January 2017. https://www.structuremag.org/article/5-over-2-podium-design/

Alexander, Christopher. A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Pérez-Gómez, Alberto, and Louise Pelletier. Architectural Representation and the Perspective Hinge. MIT Press, 2000.

Ching, Francis D. K. Building Codes Illustrated: A Guide to Understanding the 2012 International Building Code. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2012.

Osman, Michael. Design Technics: Archaeologies of Architectural Practice. Edited by Zeynep Çelik Alexander and John May. University of Minnesota Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctvtv938x.

Carpo, Mario. “Drawing with Numbers: Geometry and Numeracy in Early Modern Architectural Design.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62, no. 4 (December 1, 2003): 448–69. https://doi.org/10.2307/3592497.

Form-Based Codes Institute at Smart Growth America. “Form Based Codes Archives.” Accessed May 12, 2025. https://formbasedcodes.org/tag/form-based-codes/

Parolek, Daniel G. Form-Based Codes: A Guide for Planners, Urban Designers, Municipalities, and Developers. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008.

DPZ | CODESIGN. “Form-Based Codes Archives.” Accessed May 12, 2025. https://www.dpz.com/project_category/form-based-codes/

Alexander, Christopher. Notes on the Synthesis of Form. Harvard University Press, 1964.

Ratti, Carlo, and Matthew Claudel. Open Source Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 2015.

Carpo, Mario. “The Craftsman and the Curator.” Perspecta 44 (2011): 86–91.

Kelty, Christopher M. Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software. Duke University Press, 2008.

Picon, Antoine. The Materiality of Architecture. University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Carpo, Mario. The Second Digital Turn: Design Beyond Intelligence. MIT Press, 2021.

Yanagi, Soetsu, and Bernard Leach. The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty. Kodansha USA, 2013.

Evans, Robin. Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays. MIT Press, 1997.

Bsummers. “What Is New Urbanism?” Congress for the New Urbanism, May 18, 2015. https://www.cnu.org/resources/what-new-urbanism

Forty, Adrian. Words and Buildings: A Vocabulary of Modern Architecture. Thames & Hudson, 2000.