Models can be used to both expand a space-time reality, and define an intimacy with the project. They are caught between the real and fictional, displayed in states ranging from the uncanny to the abstract. Over time models have served as archetypes, templates, metaphors, miniatures, and simulacra. They have been used for design, marketing, establishing conquest, planning, geological predictions, structural testing, cost estimation, didactic lessons, studying acoustics, recording history and as royal calendars.

Their lineage is most directly translated through how they were conceived and what their purpose was, rather than radical physical mutations. In antiquity they originated as early as 4600 BCE, found as religious burial relics1. In ancient Greece 1:1 models were used to translate temple details to builders2. Romans had a propensity for models in military planning. The Middle Ages saw models used by master masons for cathedral constructions3. In the Renaissance models were defined by the first architects as essential to their craft, they were used as design tools, and eventual presentation tactics4. The industrial and modern eras introduced new materials and broadened the scope of models, transforming them into mediums for kinetic experimentation, political expression, and archival preservation. The rise of Patent models in the 19th century instigated the transformation of models into commodities5. At the turn of the century, virtual models were born, and with them the collapse of categories in scale.

In today’s context, the role of models continues to evolve. Model-making has emerged as a specialized industry, with emerging firms crafting high-precision physical and competition models. These models remain vital in translating spatial ideas into tangible form, offering clients a more participatory understanding of design. However, their increasing cost and complexity have made them subject to greater scrutiny, often weighed against efficiency and value within contemporary architectural practice.

Models will play a crucial role in the practice's future, especially in digital iteration, virtual reviews, and performance assessment. It will serve as the primary language through which humans and machines communicate. Unlike traditional model making, which demands meticulous planning and craftsmanship, computational tools allow machines to generate complete models with relative ease. These machine-generated models can then be refined, developed, and expanded upon by human designers.

Diagramatic or parti models are the most mutable and longitudinal forms of models. They are not scaled and can be best described as spatially conceptual. They are often metaphoric or non-direct in their relationship to the architecture being modeled. Beginning with pre-historic models of homes and tombs, these forms also include gothic labyths and architekton idea models. Their scale can shift from entire buildings meant to model heavenly bodies, to minute scraps of paper meant to evoke a formal gesture in a much larger building. They most certainly did not originate within the discipline, but have been absorbed and have become an integral part of both the digital and physical design process.

Information and technical models test and catalogue the relationship between understood and discrete parts of a project. They relate fundamentally to engineering, information, and material capabilities. They are non-heuristic and dimensionally precise duplications of the design they intend to mirror. These can either be produced at scale or a 1:1 reproduction. Today, these models are mostly digitized in virtual interface, encoded with technical specifications on their pricing, material, code, operation, construction, and location.

The presentation model is a display of works that bridges the gap between the architects and clients/public. Nowadays, specialized firms or personnel often fabricate and digitize detailed models for client reviews, final presentations, public displays, archival records, image renderings, and office decoration. They are often produced near the end of a project and are rendered in a more pristine and finite fashion. Unlike digital twins, presentation models focus on communicating with people who do not necessarily have an architectural background, and to give them a positive impression.

Study and working models are heuristic tools that enable creative futures for design. They are formal objects with a specific scale. Beginning with Greek temples, and now with paper folding, these kinds of models have broadened the exploration of form through three dimensional iterations. Both physically and virtually they are more flexible and fuzzy than the rest of the models, often torn apart or reconfigured during the design phase. They are fundamentally related to culture.

The digital twin is a 1:1 digital reproduction of a building. It aids in construction management, clash detection, and producing drawings and images. After construction, it can be used for the two primary purposes: building management and post-occupancy evaluation. Designers test different scenarios to accumulate data for their future designs, thus closing the loop between design intent and real-world performance.

The patent model was a small-scale physical representation submitted with a patent application in the United States to demonstrate a new or improved architectural design, typically before the 1880s. It marks the first case in history in which the models from the practice do not necessarily relate to representing design ideas, but make them as a product for profit. It focused on technical innovation rather than traditional aesthetics in design.

The process model is a conceptual and physical representation to illustrate or generate design decisions. As a tool to test ideas, it is conceptual and not strictly scaled. It is often metaphoric or non-direct in its relationship to the architecture being modeled. Beginning with prehistoric models or homes and tombs, these forms include Gothic labyths and architeckton idea models. They most certainly did not originate within the discipline, but have been absorbed and have become an integral part of both digital and physical design processes.

Safdie, Moshe, Safdie Architects, and image digitization by David Harris Collection of Photographs. Moshe Safdie’s Plan of Mamilla Centre. 1974. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvwork704263/catalog.

Bologna, Giovanni da. Model for Facade. 1596. Wood and wax, 148 x 135 x 32 cm. Museo dell’Opera del Duomo. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvsite49653/urn-3:FHCL:9463691/catalog.

Town, Ithiel, and Yale engineering students (model making). Model of Lattice Truss. 1928. https://jstor.org/stable/community.14633596.

Avner, and Israel Sun Ltd. Architecture Students at the Technion Building a Shell Structure. 1969. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/JPCDISUN1000/catalog.

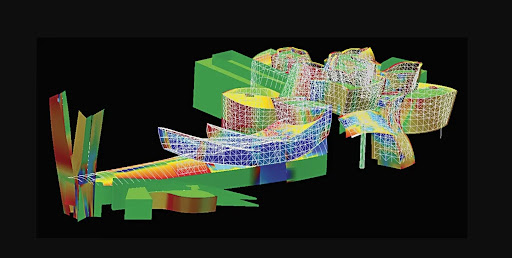

Gehry, Frank, and Gehry Partners, LLP. Digital Render of the Guggenheim Bilbao. 1997. Digital rendering. https://www.artforum.com/features/frank-gehry-talks-with-julian-rose-238794/.

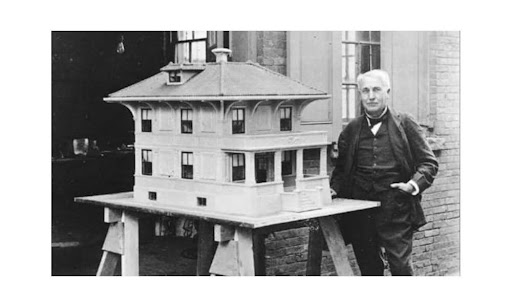

Thomas Edison with a Model for a Concrete House. 1910. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Edison/Menlo-Park#/media/1/179233/75746.

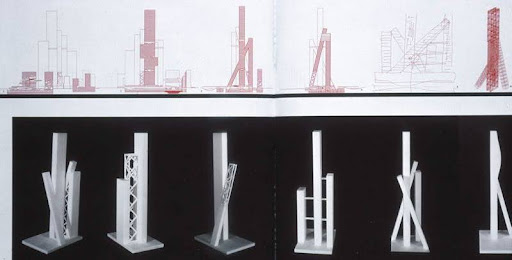

Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rem Koolhaas, and Bates Gary. Study of Skyscraper. 1998. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/olvwork97699/urn-3:GSD.loeb:843401/catalog.

Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig, Yujiro Miwa, Henry Kanazawa, and Pao-Chi Chang. Convention Hall. 1953. http://id.lib.harvard.edu/images/8000898349/catalog.

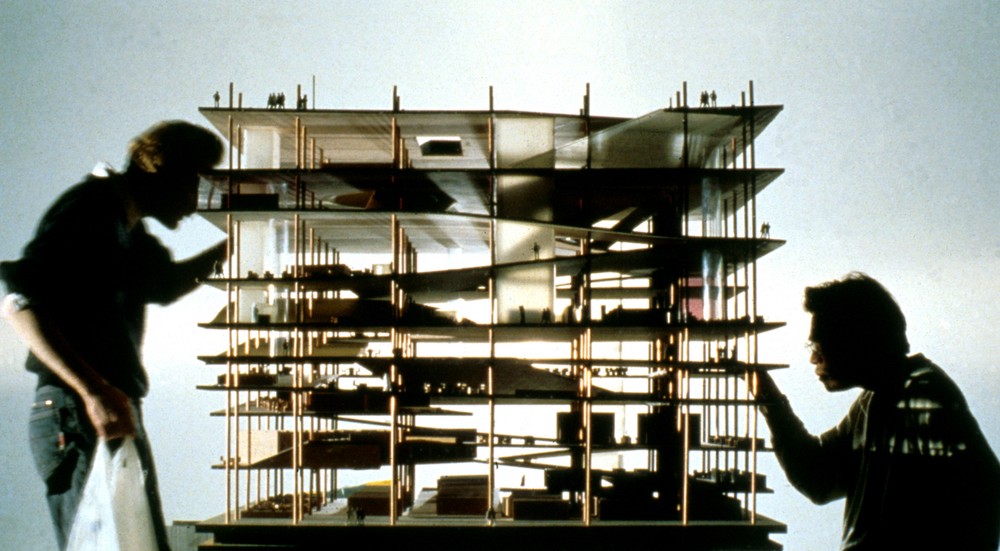

OMA. Jussieu Library Model. 1992. https://www.oma.com/projects/jussieu-two-libraries.

The profession has yet to form, models are often used in burial and religious ceremonies.

The Renaissance births the profession and Alberti writes about models as integral to architectural design, presentation, and construction.

The late Renaissance brought about a decline of the design model and a rise in the presentation model. Also interest in the architecture of antiquity led to a surge of cork and plaster anthropological models.

Modernism saw a resurgence of the study model in finding new forms, tectonics, and logics. The abstract model also played a part in some political transitions.

The digital model arrives. Analogue,Design, and presentation uses are merged and blurred into virtual duplicates. Today many design primarily through the model on a screen. Its use as a single source of truth also complicates issues of ownership and authorship. In visualization the technologies of VR and AR are pushing it to even more polygonal fidelity and use diversity.

The role of models in architecture practice has changed drastically over the last few decades. Development in computation and virtual reality (VR) technology began to optimize work processes using both physical and virtual forms of models. Models still stimulate architects’ design thinking as they have done for thousands of years, but the new technologies have radically improved speed, cost efficiency, affordance, and intuitiveness. An increased number of tests via digital models (both abstract and detailed) results in more iterations being available. Current AI technology can rapidly calculate optimized massing and circulation that abide by the local zoning rules and codes, based on the given FAR and program. These digitally and virtually generated models also enable easy assessment of the performance of future buildings, such as lighting, ventilation, energy efficiency, traffic management, and structural viability, in the form of digital twins.

Mario Carpo, in his lectures and writings, stated the difference between the way machines and humans work. Machines work in a way that humans think impractically. Traditional designs, including architectural, require a solid thinking process and several rough iterations. Humans choose the best option, considering the qualifications, and then develop it into a blueprint. However, machines, thanks to their unbelievable calculation speed, just run enormous amounts of trials and assess errors for each iteration. Models are a key tool for communicating with machines. Architects produce drawings, not buildings. They use drawings as a main communication tool to speak with the client, builders, and the public. Machines read through digital models. They can read in 3D and generate quick responses in 3D as well.

The application of AI and VR technology in architectural model-making should bring a much more significant impact than BIM brought to the profession many years ago. BIM changed how architects think and perform, and cherished design thinking in objects rather than the composition of 2D drawings. In some aspect, it knocked down the notion of a master builder, as it enabled the design process to be intuitive and accessible to many people, including entry-level designers. Nonetheless, BIM modeling is not fully artificial as human labor should be involved in commanding every single detail under the current BIM workflows. How should architects use these new and highly efficient tools wisely? How can we not lose our original ideas in the name of efficiency and automation? While AI and VR technologies will continuously revolutionize the practice of architecture by enhancing performance, speed, and accessibility, we, as architects, must actively reinterpret their role to preserve creativity and critical thinking within this new design paradigm.

Works Cited

The sand table model has a long and multifaceted history, with applications spanning military strategy, urban planning, architectural design, education, and psychotherapy. While digital and virtual simulations increasingly replace physical sand tables, their core function remains unchanged: to shrink, visualize, abstract, and render space intelligible and controllable. The sand table is not a neutral representational tool—it is a material manifestation of spatial power, one that reveals who commands space, who constructs its narrative, and who decides what can be seen and by whom.

A sand table presents a world in miniature—a scaled-down environment that turns complex, lived space into something graspable and manipulable. It reverses the historic relationship between people and their environment, where once the built or natural world overwhelmed perception and decision-making, the sand table compresses that world into a surface for observation and action. It offers a panoptic view. The sand table’s bird’s-eye perspective enacts a kind of spatial surveillance: the model is observed from above, interpreted by experts, and acted upon as if its reality were already fixed and knowable.

In military applications, the sand table allows commanders to “step outside the battlefield,” simulating troop movements and logistics as if from a detached, all-knowing vantage point. In urban planning, it provides a visual structure for comprehending relationships at metropolitan scales, offering designers, developers, and officials a shared visual platform through which to propose interventions. In both cases, the sand table is not merely a record of what exists, but a projection of what should exist—a tool that edits and overwrites reality rather than reflecting it.

The sand table is a freeze-frame of space. It denies process, contingency, and temporality. Museum dioramas may re-stage a historical moment, while planning models previsualize an idealized, speculative future. But whether anchored in the past or future, the sand table erases the dynamism of lived environments. It displays space not as lived, but as disciplined—immobile, silent, and subject to design. The model-maker thus occupies a position of authorship and authority, projecting subjective judgments, ideological values, and political priorities into the static model.

The sand table is also an abstraction of reality—a product of selective vision. Elements irrelevant to the central design narrative—informal economies, marginalized populations, architectural entropy—are filtered out. Every model performs a form of visual discipline, organizing what is allowed to be seen and what must remain invisible. Here, we see Foucault’s insight that power operates through regimes of visibility: that which is visible can be managed, ordered, and controlled, while that which remains unseen falls outside the realm of knowledge and action.

Thus, the sand table functions not only as a design or pedagogical tool but as a diagram of governance. It transforms complex spatial realities into legible surfaces, suited for intervention and investment. In doing so, it reinforces specific spatial hierarchies, excludes alternative narratives, and encodes a spatial logic of authority. The sand table does not simply depict the world—it disciplines it.

Works Cited

The architectural model alone can embody and communicate ideas of the architect of a new or altered future; however, when documented in photography or in exhibitions, the model can take on a new role of establishing the presence of the architect in society. The inquiry reveals that the presentation of the model has concerned the architect since Leon Battista Alberti, who advocated for “plain and simple” models to focus the attention of the public on the concept and ideas of the architect as opposed to the model maker’s ability to replicate details in miniature.

Through the modern movement, the image or photograph of models has been strategically orchestrated to present a view of the architect that is both heightened and homogenous, while celebrating the architect’s ability to make simple the complexity of the building, the city, and life. Despite the contemporary trend towards the digital, a generation of rising architects have returned to the model and specifically the crafting of the image of the model to establish a space within the discipline of architecture.

The model thus is not simply operating as a tool for investigating and communicating ideas but takes on a performative role. The investigation will similarly examine how communities of Black design professionals have begun to use the model in exhibition settings to project not only their presence within the discipline but also new roles and relationships of the architect as an agent in society and the cultural realm. With hopeful architecture students emerging out of school into a profession that does not easily accept the new and unestablished, finding a means to project a presence in the discipline, the profession, and society can become a means of attaining agency.

Works Cited

How do full scale mock-ups participate in a temporal framework that informs the architectural design process? Our research focuses on the employment of full-scale models in the production of architecture throughout history. Mock-ups have been discussed in terms of templates, proof-of-concept, and performance simulations, implying a temporal use before, during, or after the construction of the building. In the traditional employment of mock-ups, specific properties of the total built work can be isolated, tested and recreated, and applied back to the building. Increasingly, however, the digital twin now begins to take over not just as a full-scale 1:1 virtual replica, which beyond instructions for building construction can produce scientific measurements, views and other output that take the place of the material mock-up. More importantly, as it pertains to our research inquiry into temporal frameworks, digital twins act as “simulators for real-time prediction, optimization, monitoring and controlling” a physical asset, suggesting a new temporality of “real-time” that is constant throughout the entire lifespan of a building.

Works Cited

Digital twins can be understood as a modern counterpart to the full-scale mock-up by marking an inflection point between design and construction as two distinct modes in the building process. The digital twin model, like the BIM model before it, promotes the blurring or fusion of these two seemingly distinct modes, which has implications for how architects define their role in the built environment. If the constructed building can continue to “talk back” through sensory feedback, who has the authority to attend to the building’s future needs, whether they be structural, mechanical, or aesthetic? Because the digital twin concept is still a relatively new development, there are multiple models for answering this question. By 2050, digital twin systems will have become an industry standard for AEC, moving beyond descriptive or informative digital replicas and into increasingly sophisticated predictive or even autonomous models that incorporate artificial intelligence and machine learning. Among the principal drivers of this acceleration are the members of the Digital Twin Consortium, representing over 200 organizations across technology, healthcare, finance, manufacturing, infrastructure, defense, government, and academia; firms with a specific AEC focus make up roughly a third of these organizations, including Autodesk and ESRI. The overwhelming majority of these firms define the value of digital twins in terms of reducing cost of design and construction, minimizing risk, and increasing value for clients and owners. What other value systems are pushed aside or left out in this trajectory? Where, how, and on behalf of whom can architects assert agency in the digital twin ecosystem?

Works Cited

In many ways, BIM represents a foundational shift in many long-held givens of the AEC environment. BIM radically alters longstanding linear workflow norms and torpedoes contractual standards. BIM’s most basic functionality further solidifies a product-oriented approach to Architecture and hails the death the architectural drawing. Yet all this is not without cause; undoubtably BIM provides great leaps in design and construction efficiency, environmental performance, operating efficiency and numerous other sectors.

Architects have resisted and continue to resist BIM’s incursion. Ostensibly this is because the additional burden of BIM’s implementation and coordination is financially untenable under old fee structures, but it also eliminates the long cherished ideal of the master builder and unilateral creative freedom. Additionally, BIM’s assembly-of-component nature undercuts long held modernist values of abstract formalism (bordering on material homogeneity and ambivalence). Yet as Peggy Deamer notes, if embraced by and incorporated into the academy, BIM could provide new opportunities for creative expression (and when necessary, subversion). Without a doubt, BIM is here to stay.While at the moment its gains are only absolutely necessitated at one extreme of Indaba’s “Bigness,” BIM is trickling down to smaller and smaller projects. Following this research, architects’ and especially architecture students’ aversion BIM seem to me like aversions to gravity.

During my time in grad school, I have worked part time as an MEP Coordinator and Assistant Superintendent for a General Contractor in Boston. This experience in combination with my M.Arch program provided me two poles to understand and critique aspects of the increasingly BIMmed AEC world. For, as tight as buildings are becoming, I am familiar with navigating and dimensioning BIM models and finding altogether different built realities. This work provided me a conceptual underpinning for those issues and the work more generally. Like construction itself, the BIM workflow seems mostly circling around until the requisite tolerance is met.

Yet, from an architecture student’s perspective, I can’t help but lament, at least a little, the reign of BIM. As practiced, BIM does seem to channel work into existing ruts. The path of least resistance is the available mullion or the furniture layout block you used on the last project, all in the name of efficiency.

Works Cited

A Catalogue of the Paintings, Sculptures, Architecture, Models, Drawings, Engravings &c.: Now Exhibiting under the Patronage of the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, at Their Great Room in the Strand. London: Printed by James Harrison, opposite Stationers-Hall, Ludgate-Street, 1764. https://go-gale-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/ps/i.do?p=ECCO&u=camb55135&id=GALE|CB0127760693&v=2.1&it=r&sid=primo.

Ulrich, Roger B. A Companion to Roman Architecture. 1st ed. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. 2013.

Siebein, Gary W. "A Comparison of Architectural Acoustic Scale Models to Their Prototype Room." The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 70, no. S1 (1981): S44.

Pattinson, Graham Day. A Guide to Professional Architectural and Industrial Scale Model Building. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1982. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015002903535&view=1up&seq=5.

Cremer, Annette. "A Miniature State: The Dollhouse City of Princess Augusta of Schwarzburg (1666-1751)." The Court Historian 20, no. 2 (2015): 167-86.

Meredith, Michael. "AFTER AFTER GEOMETRY." Architectural Design 83, no. 2 (2013): 96-103.

Ceccato, Cristiano, Lars Hesselgren, Mark Pauly, Helmut Pottmann, and Johannes Wallner. Advances in Architectural Geometry 2010. Berlin: Ambra Verlag, 2016. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=1893534&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

“Aktuelle Nachrichten / News.” Atelier Dieter Coellen. Accessed May 27, 2020.

Carazo Lefort, Eduardo, and Noelia Galvan Desvaux. "Aprendiendo Con Maquetas. Pequeñas Maquetas Para El Análisis De Arquitectura; Learning with Models. Little Models for the Analysis of Architecture." 19, no. 24 (2014): 62-71.

“Architectural Model.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation, April 11, 2020.

Smith, Albert. Architectural Model As Machine: A New View of Models from Antiquity to the Present Day. Jordan Hill: Taylor & Francis Group, 2004. Accessed May 26, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Dunn, Nick. 2014. Architectural Modelmaking. Vol. Second edition. London: Laurence King Publishing. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=e000xna&AN=910072&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Janke, Rolf. Architectural Models. New York: Architectural Book Pub., 1978.

Knoll, Wolfgang, and Hechinger, Martin, Author. Architectural Models Construction Techniques. 2nd ed. S.l.], 2007.

Museum, Albert, and Digital Media. “Architectural Models in the V&A and RIBA Collections.” Architectural Models in the V&A and RIBA Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum, Cromwell Road, South Kensington, London SW7 2RL. Telephone 44 (0)20 7942 2000. Email vanda@vam.ac.uk, January 31, 2013. http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/a/architectural-models-in-the-v-and-a-and-riba-collections/.

Forman, Robert. Architectural Models. Make It Yourself. London & New York: Studio, 1946.

Delidow, Margo. “Architectural Models: Materials, Fabrication, and Conservation Protocols.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 52, no. 1 (2013): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1179/0197136012z.0000000001.

Doshi, Balkrishna V., Snehal. Shah, and Akshara Foundation. Architectural Models: Works of Architect Balkrishna Doshi. Ahmadabad: Akshara Foundation, 2003.

Stavrić, Milena, Predrag Šiđanin, and Bojan Tepavčević. Architectural Scale Models in the Digital Age: Design, Representation and Manufacturing. Wien, Austria; New York: Springer, 2013.

Porter, Tom., and John Neale. Architectural Supermodels: Physical Design Simulation. Oxford, England: Architectural Press, 2000.

Schilling, Alexander. Architecture and Model Building: Concepts, Methods, Materials. Basel: Birkhäuser, 2018.

Schilling, Alexander. Architecture and Modelbuilding: Concepts, Methods, Materials. Basel/Berlin/Boston: Birkhauser Verlag GmbH, 2018. Accessed May 26, 2020. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Payne, Alina. “Architecture: Image, Icon or Kunst der Zerstreuung?”. Das Auge der Architektur. Ed. A. Beyer. Berlin: Fink Verlag (2010). 3-39.

Pocobelli, Boehm, Bryan, Still, and Grau-Bove. "BIM for Heritage Science: A Review." Heritage Science, 2018, Heritage Science , 6 , Article 30. (2018).

Burry, Mark. Blurring the Lines: Architecture in Practice. Chichester, England; Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2006.

King, Ross. Brunelleschi's Dome: The Story of the Great Cathedral in Florence. London: Chatto & Windus, 2000.

Cat'zArts - Résultats de recherche. Accessed May 27, 2020. http://www.ensba.fr/ow2/catzarts/rechcroisee.xsp?f=Auteur_field&v=Rosa,+Agostino&e=.

Guo, Boya, John May, and Harvard University. Graduate School of Design. Critical Chinese Copying: Authenticuty & Originality in the Built Environment of Contemporary China, 2017.

Stoddart, Simon, Anthony Bonanno, Tancred Gouder, Caroline Malone, and David Trump. "Cult in an Island Society: Prehistoric Malta in the Tarxien Period." Cambridge Archaeological Journal 3, no. 1 (1993): 3-19.

Fargo, Jason. "Designer Dollhouse." I.D. [USA] 48, no. 2 (2001): 14.

Sun, Lei, Tomohiro Fukuda, Toshiki Tokuhara, and Nobuyoshi Yabuki. "Differences in Spatial Understanding between Physical and Virtual Models." Frontiers of Architectural Research 3, no. 1 (2014): 28-35.

Garofalo, Luca., and Peter Eisenman. Digital Eisenman: An Office of an Electronic Era. Basel; Boston; Berlin: Birkhäuser, 1999.

Picon, Antoine, Chandler Ahrens, and Aaron Sprecher. "Digital Fabrication, Between Disruption and Nostalgia." In Instabilities and Potentialities: Notes on the Nature of Knowledge in Digital Architecture, 223-38. 1st ed. Routledge, 2019.

Iwamoto, Lisa. Digital Fabrications :architectural and Material Techniques. Architecture Briefs. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2009.

Lindsey, Bruce, and Frank O. Gehry. Digital Gehry: Material Resistance, Digital Construction. IT Revolution in Architecture. Basel; Boston; Berlin: Birkhäuser, 2001.

Constanzo, Gerald. "Dollhouse Technique Focuses on Building Dreamhouses." Marketing News 18, no. 16 (1984): 15.

Harvey, Justine. "Edible Architecture." Interior, no. 13 (2014): 94-95.

Ryan, Raymund. "Empirical Affinities." The Architectural Review 232, no. 1388 (2012): 102-03,4.

Nilsson, Fredrik. "Exploring Architectural Knowledge by Making and Reconstructing Historical Artefacts." 10-24. 2016.

Hastie, Amelie. "History in Miniature: Colleen Moore's Dollhouse and Historical Recollection." Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 16, no. 3 (2001): 112-157.

Paes, Daniel, Eduardo Arantes, and Javier Irizarry. “Immersive Environment for Improving the Understanding of Architectural 3D Models: Comparing User Spatial Perception between Immersive and Traditional Virtual Reality Systems.” Automation in Construction 84 (2017): 292–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2017.09.016.

Carazo Lefort, Eduardo. "La Maqueta Como Realidad Y Como Representación. Breve Recorrido Por La Maqueta De Arquitectura En Los 25 Años De EGA; Models, Reality and Representation. A Brief Tour through the Architectural Model in EGA’s 25-year Print Run." 23, no. 34 (2018): 158-171.

Rykwert, Joseph. Leonis Baptiste Alberti. Architectural Design; v. 49, No. 5-6. London: Architectural Design, 1979.

Sheil, Bob. Manufacturing the Bespoke: Making and Prototyping Architecture. AD Reader. Chichester: John Wiley, 2012.

Carazo Lefort, Eduardo. "Maqueta O Modelo Digital. La Pervivencia De Un Sistema.; Scale Model or Digital Design Model. The Survival of a System." 16, no. 17 (2011).

Thorne, James Ward, Kathleen. Culbert-Aguilar, and Michael Abramson. Miniature Rooms: The Thorne Rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago. 2nd ed. Chicago, Ill.: Manchester, Vt.: Art Institute of Chicago; Distributed by Hudson Hills Press, 2004.

Mikula, Maja. "Miniature Town Models and Memory: An Example from the European Borderlands." Journal of Material Culture 22, no. 2 (2017): 151-72.

Mullane, Matthew. "Model Tenants: Tokyo's Archi-Depot." Log, no. 39 (2017): 39-43. Accessed May 29, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/26323999.

Model of the Temple at Paris, with its various buildings, and the tower in which the King, Queen, and royal family of France, have been imprisoned since the 13th of August. S.n., [1792]. Eighteenth Century Collections Online, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/CW0104861877/ECCO?u=camb55135&sid=ECCO&xid=7852da2b. Accessed 26 May 2020.

Horden, Richard. "Models through Time." The Architectural Review 232, no. 1387 (2012): 96-97,4.

Carpo, Mario. 2019. “Particlised: Computational Discretism, or The Rise of the Digital Discrete.” Architectural Design 89 (2): 86–93. doi:10.1002/ad.2416.

Breisch, K. "Oriel Prizeman. Philanthropy and Light: Carnegie Libraries and the Advent of Transatlantic Standards for Public Space." The American Historical Review 118, no. 3 (2013): 821.

Abkowitz, Alyssa. "RJ Models's Flashy Replicas of Luxury Homes; The Model-maker Creates Intricate Designs from Its Workshop in Shenzhen, China." Wall Street Journal (Online) (New York, N.Y.), 2015.

Liefooghe, Maarten. 2019. “Tactically Ambiguous Performance: The 1:1 Model of Mies’s Krefeld Golf Clubhouse Project by Robbrecht En Daem Architecten.” Journal of Architecture 24 (3): 340–65. http://search.ebscohost.com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bvh&AN=811447&site=ehost-live&scope=site.

Retsin, Gilles. 2017. “Teapots, Dresses and Chairs.” Architectural Design 87 (6): 126–33. doi:10.1002/ad.2248.

Mindrup, Matthew. The Architectural Model: Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, the Exemplar and the Muse. Cambridge, Massachusets: MIT Press, 2019.

Wilton-Ely, John. "The Architectural Models of Sir John Soane: A Catalogue." Architectural History 12 (1969): 5-101.

Busch, Akiko. The Art of the Architectural Model. 1st ed. New York, NY: Design Press, 1991.

Carpo, Mario. "The End of the Digital." Harvard Design Magazine, no. 35 (2012): 167-90.

Hendrick, Thomas William. The Modern Architectural Model. London: Architectural Press, 1957.

Fok, Wendy W, and Antoine Picon. "The Ownership Revolution." Architectural Design 86, no. 5 (2016): 6-15.

Columbano, Alessandro, and Michael Dring. “The Pedagogy of Using a RP Architectural Model.” Virtual and Physical Prototyping 5, no. 4 (August 2010): 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/17452759.2010.528842.

이주현. "The Power of Architectural Models in Museums." 박물관학보, no. 27 (2014): 79-109.

Jerlei, Triin. "The Secret Dollhouse: Craft and Resistance in Stalinist Estonia." The Journal of Modern Craft 10, no. 2 (2017): 157-74.

Alberti, Leon Battista, Cosimo Bartoli, and Giacomo Leoni. The Ten Books of Architecture : The 1755 Leoni Edition. New York: Dover Publications, 1986.

Albee, Edward, and Billy Rose Theatre. Tiny Alice: A Play. New York: Dramatists Play Service, 1965.

Busch, Akiko. "True or False: Model Photography Is High Art." Architectural Record 180, no. 5 (1992): 34.

Hill, David. "Unveiling the Models of Brad Cloepfil." Architect 105, no. 2 (2016): 65.

Moloney, Jules. "Videogame Technology Re-Purposed: Towards Interdisciplinary Design Environments for Engineering and Architecture." Procedia Technology 20 (2015): 212-18.