Drawings are a form of communication, helping to translate design ideas into built form. With a full set of drawings, the architect can express complex designs with a higher degree of detail and precision than other forms of architectural representation. Drawings may convey scales from the site layout to the wall assembly and contain information from the atmospheric to the quantitative.

During the Renaissance, drawings helped catalyze the architect’s shift from craftsman to intellectual. Alongside the humanist pursuit of science and knowledge, architects became professionals, academic and learned. During this period, the triumvirate of the plan, section, and elevation were codified in treatises as architectural representation with norms and conventions. Furthermore, fifteenth-century painters’ experiments with methods of linear perspective brought about new investigations of systematizing three-dimensional space to generate perspectival images1. Later, the axonometric was popularized as a form of three-dimensional projection that maintained precise measurements2. In modern practice, the diagram, collage, and montage have developed alongside drawing to depict notions of time, movement, and realism into the architect’s representation.

Shifts in technology have changed the role of the architectural drawing in design, although the plan, section, and elevation remain integral to the practice. Throughout most of history, architects drew two-dimensional orthographic projections, which could be combined to represent a three-dimensional project. As computer-aided design has popularized 3D modeling as a design tool, drawings are increasingly an artifact of the modeling process, being “cut” and projected flat.

The constructed perspective is a measured architectural drawing which represents real space through an illusion on a two-dimensional page. It uses mathematicised recession to construct an image that recedes in space to a single point.

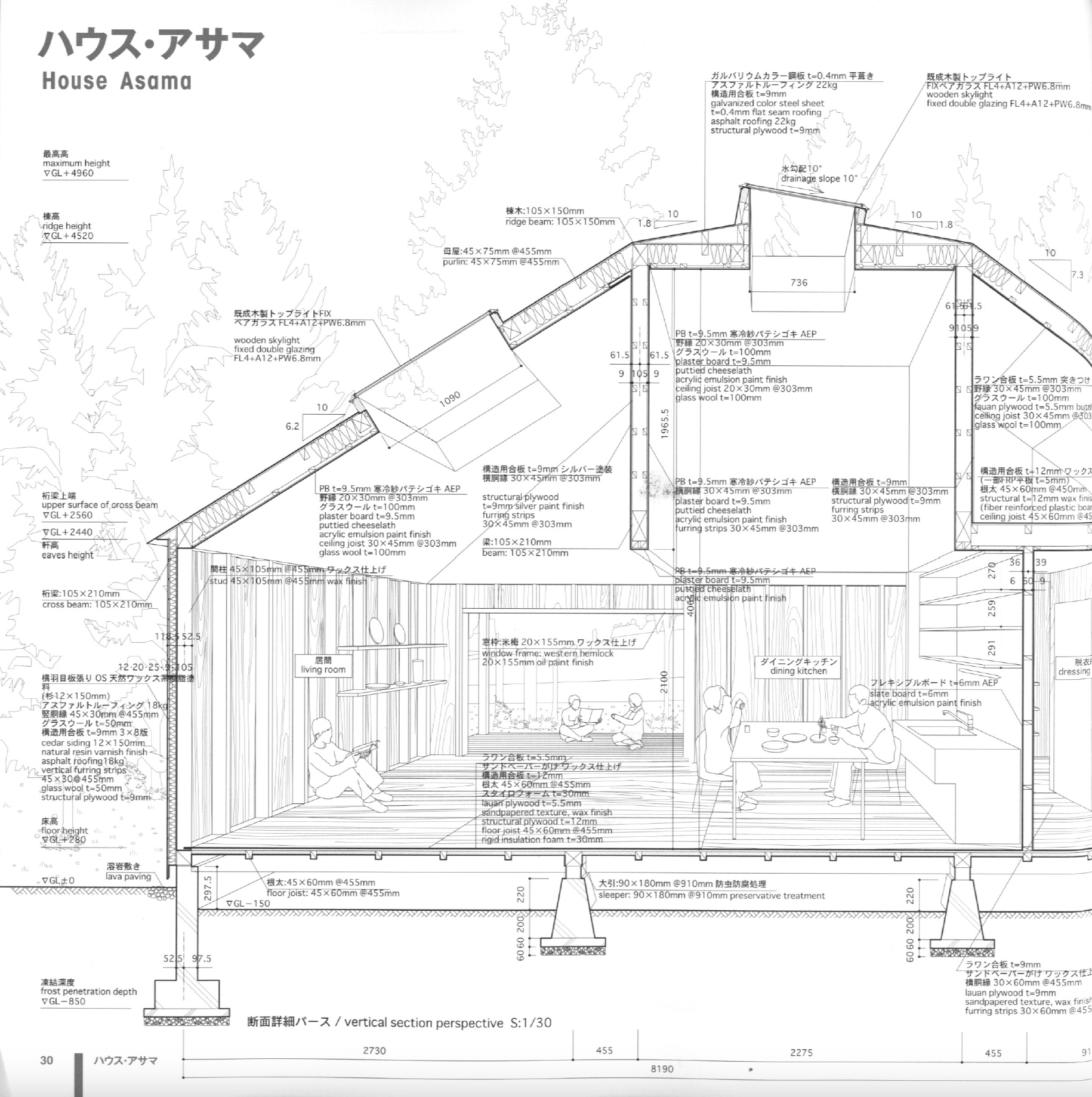

An architectural detail is a highly detailed drawing showing the juncture at which varying and diverse materials meet in a building. It is most often depicted in orthographic projection but can appear as a constructed perspective.

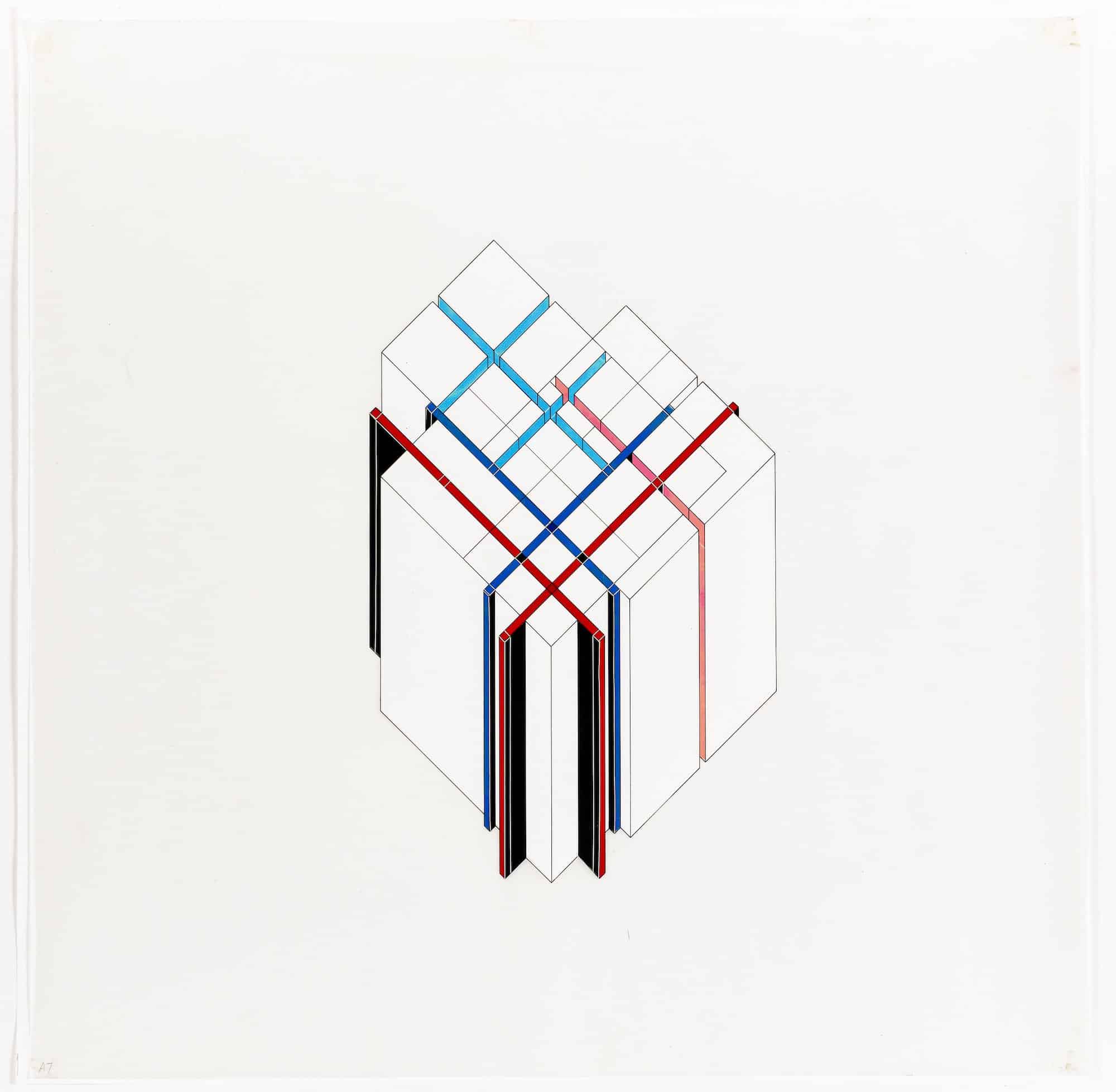

Orthographic projection utilizes parallel line to create measured drawings. Plans, sections, and elevations are primary projections that favor one side of an object. The axonometric is created by rotating the object to reveal multiple sides of the object, depicting three-dimensional space.

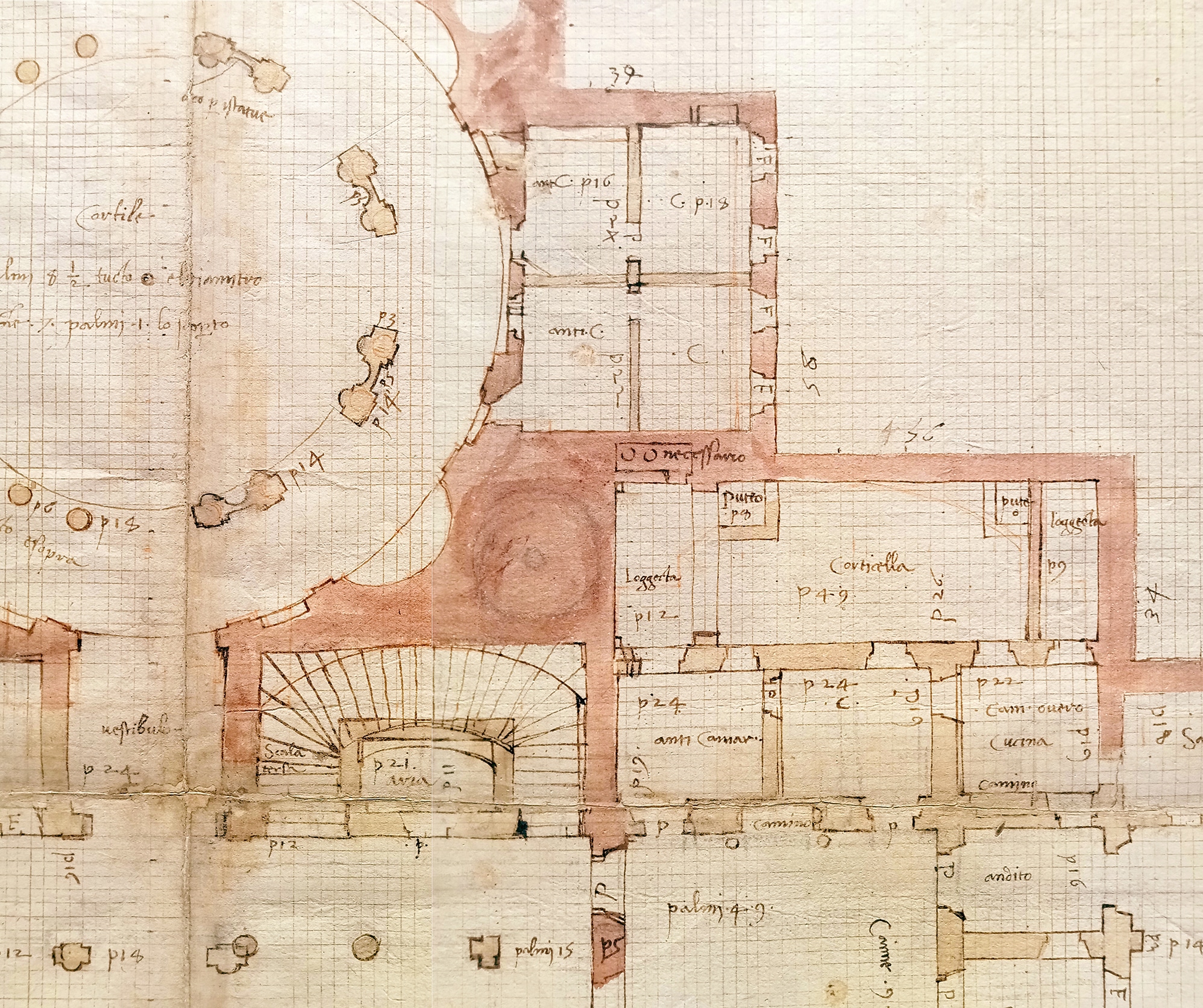

Peruzzi, Baldassare. Plan for Palazzo Orsini. 1519. Ink, Red Chalk and Watercolour on Squared Paper, 57.8 x 80.7cm. F.456A. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence, Reproduced with the permission of the Ministry of Culture.

Mayne, Thom, and Andrew Zago. Sixth Street House Project. 1987. MoMA Department of Architecture and Design.

Politecnico di Milano. Società Umanitaria Archive Drawings and Current Situation Survey by the Master Course of Architettura Delle Costruzioni at Auic School. 2021 2019.

Rudolph, Paul. Art and Architecture Building, Yale University, New Haven, CT. 1958. Ink on Board, 30 x 40 inches. MoMA.

Atelier Peter Zumthor & Partner AG. “Shelter Roman Archaeological Site, Drawing.” In Peter Zumthor Works: Buildings and Projects 1979-1997, 1999, by Peter Zumthor and Helene Binet. Basel: Birkhauser, 1985.

Peruzzi, Baldassare. Plan for Palazzo Orsini. 1519. Ink, Red Chalk and Watercolour on Squared Paper, 57.8 x 80.7cm. F.456A. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, Florence, Reproduced with the permission of the Ministry of Culture.

Vasari, Giorgio. Paul III Supervising the Work on Saint Peter’s Basilica, Palazzo Della Cancelleria, Rome. 1546.

Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig. Neue Wache War Memorial Project, Sketch, Interior Perspective View. 1930. Pencil on Paper, 8 1/4 x 13 inches. MoMA, Artists Rights Society, VG Bild-Kunst.

Tschumi, Bernard. Parc de La Villette, Exterior Perspectives, Sketch. 1983. Ink on Paper, 11 5/8 x 16 1/2 inches. MoMA.

Atelier Bow-Wow. “House Asama.” In Graphic Anatomy: Atelier Bow-Wow. Tokyo: Toto Publishing, 2007.

Nishizawa, Ryue, and Office of Ryue Nishizawa. Moriyama House, Tokyo, Japan, Ground-Floor Plan. 2005 2002. MoMA Department of Architecture and Design.

Eisenman, Peter. House VI, Color Axonometric. 1972. 1280. Drawing Matter Collection.

Giovanni Battista Bertani, Detail of Ionic Order in Silhouette with Incised Drawing of Volute, 1554-1556, Mantua, Casa dei Bertani, Facade (Klaus Bergheimer in “‘An Impression Made on the Ground, Either in Dust or Paste or Snow’ Mediums of Architectural Drawing at the Dawn of Paper-Based Design”)

The drawings that we know from antiquity are either plan or elevation, or a combination of the two, engraved on stone, clay or drawn on papyrus

Surviving documentation of drawings from the middle ages is scarce. The most prominent is a plan drawing for the Monastery of St Gall

The soaring, porous facades of High Gothic churches were met with detailed, large format detailed elevation drawings, often with many sheets of paper stitched together.

The birth of constructed perspective occurs early in the renaissance with Brunelleschi, and the triumvirate of plan, elevation, and section was systematized. Sculputed details are often rendered in perspective for mansons.

After its development in military strategy, the axonometric, with its three dimensional properties as well as its measurability, was a significant form for architecture in the industrial revolution. This era also sees a rise in literacy accross the western world with allows architects to communicate to builders through specificaitons.

The birth of modernism produced a focus on the plan and interior perspective. As new materials are introduced, the detail rises in importance.

After the second world war, the axonometric reemerged as a significant drawing for comprehensions of details and space. On a larger scale, the drawing was used to express new forms of urban subjective experience replacing the perspective as a constuction tool.

The digital age in architecture produced complex three-dimensional forms rendered in two-dimensions, while this could lead to a resurgence of constucted perspectives, instead court rulings dictated that writing superceed drawing leading to an explosion of specifications.

Architectural drawing is both an act and the artifact it produces. It is a tool for communication with collaborators, clients, and builders, and for the design process itself: translating thoughts into form, movement, and construction assemblies. In education and in historical archives, these artifacts of process are often cherished: sketches, diagrams, and alternate visions that give a glimpse into the architect’s mind before the final design or building is complete. Within professional practice, however, the drawing is a specific type of document, an Instrument of Service: tied to the legal operation of the profession, rather than the act of design. This definition of drawing is agnostic to the existence of process drawings—they are merely by-products of architectural practice.

To unpack this relationship, it is useful to situate the architectural drawing with respect to these by-products. These products can be mapped out in a plot along two axes, with the orthographic projection positioned at the center of four descriptors: informational versus experiential, and artifact versus process. The orthographic projection persists as the dominant form of architectural drawing because it adheres to descriptive conventions to communicate to a disciplinarily literate audience (informational) while relating parts visually to convey a spatial understanding (experiential). As a document, it is both a part of the making of a building (process) and the final product of the act of design (artifact). Through the articulation of its qualities, we can understand the related but distinct roles of the other drawing products: the diagram, the detail, the sketch, and the constructed perspective, as well as the moment when the role of drawing is overtaken by other products of practice: specification and image.

As the fundamental nature of architectural drawings has changed little over time, still primarily in the form of orthographic projections composed of linework, dimensions, and details, it is the by-products of practice that reveal the radical shifts in the design process, and their resulting impacts on the designs themselves. Over the past few decades, digital technologies have fundamentally changed how most architects work, enabling a new pace of production, scale of iteration, and in many cases, inverting the relationship between drawings and models. Plans and sections are increasingly replaced by three-dimensional models, which are then converted into two-dimensional drawings as needed. Thus, the act of drawing is often removed from the production of the drawn artifact, and sometimes, from the process of design itself. Although these changes have only marginal effects on primary products like construction documents, they can result in entirely different by-products of design. Layers of trace paper are replaced by the version history of digital files. Constructed perspectives are overtaken by rendered views. As workflows continue to shift with the integration of BIM software and artificial intelligence, the by-products of practice are the carriers of change in architectural thinking and in the labor of architectural work.

Works Cited

Drawing, as the architect’s method of translating ideas to built form, can be dated back to as early as antiquity. While it is a centuries-old practice, the means of producing a projection as a representation of three-dimensional space has continuously evolved alongside key technological developments from the Renaissance and the Enlightenment to the introduction of computer-aided design. Going from a drawing on paper to drawing on an interface has undoubtedly shifted the boundaries of architectural drawing from an action that is confined to limitless.¹ How have the technologies that ease the discrepancies between two and three dimensions influenced the way we think of drawing as a tool and consequently, drawing as a product of practice?

Given how the foundations of architectural drawing are disseminated through education, an analysis of representation course syllabi at the GSD throughout the 2000s begins to paint a picture of how the discipline of drawing is constantly being revised to address the changing landscape of practice. In the early 2000s, drawing was taught through two courses, the technical Visual Studies and theoretical Projective Representation in Architecture. In Visual Studies, students developed skills of representing space on two-dimensional surfaces through freehand drawing. This was supplemented by Projective Representation in Architecture, a seminar which examined the history, theory, and practice of drawing as it has evolved throughout the decades to understand how projection has shaped the practice for students to chart the future.

In 2010, the language used to describe the Visual Studies course shifts to elaborate on the importance of developing freehand drawing techniques alongside digital processes. Peter Lynch suggested that “Architects who are fluent in various kinds of freehand drawing are able to generate, refine, and evaluate design ideas more effectively than architects who depend upon the computer for visualization.”² During this semester, the course Digital Media I began being offered to students to introduce tools of parametric and generative geometry and modelling as a means of solving and communicating design intent.

From 2018 to the present, drawing has been taught in two modules: Architectural Representation I and Architectural Representation II. In Architectural Representation I: Origins + Originality, conventional techniques of orthographic drawing are analyzed as integral to the design process, but the course begins a conversation upon the limits of the techniques and encourages students to consider “representational riffs emerging in response to the contemporary context.”³ The following module, Architectural Representation II: Projective Realities, specifically explores the geometric logics that discipline architecture, and perhaps how understanding geometries in two dimensions (drawing) and three dimensions (construction) illuminates and begins to resolve the conflict between architecture as science and architecture as representation.

From these course descriptions, it appears that the foundations of drawing are still understood as orthographic drawing; however, geometric modelling methods have become more prevalent early in the architect’s studies as a requisite skill to develop ideas. This appears to reflect the realities of practice, in which the digital model has become increasingly important in the design process given its ability to facilitate communication between architects, contractors, and clients.⁴ As a result, drawing is oftentimes the byproduct of the digital model for the sole purpose of completing construction documents. Rather than thinking of drawing as a product of the past, perhaps the lines drawn between products of practice are not so distinct—where drawing, image, and modelling can be grouped under a branch of Visual Representation.

Works Cited

Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “Visual Studies.” Courses. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/visual-studies-fall-2010/

Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “Architectural Representation I.” Courses. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/architectural-representation-i-fall-2018/

Ng, Morgan. “An Impression Made on the Ground, Either in Dust or Paste or Snow: Mediums of Architectural Drawing at the Dawn of Paper-based Design.” In Building With Paper: The Materiality of Renaissance Architectural Drawings, edited by Dario Donetti and Cara Rachele. Brepols, 2021.

Scolari, Massimo. Oblique Drawing. The MIT Press, 2012.

This is a drawing. It contains raw information in the form of generative data which, when processed, results in a specific instance of a physical object; that is an image. Much like an organism grows through instancing its genetic code, a dish is imaged by a chef through following a recipe, or a symphony is instanced by its players reading a score, an architect images a building from its construction document set. An organism cannot exist without DNA, the chef does not create a recipe by first eating the finished dish, a symphony does not write the score, nor does the architect create a construction document set by looking at a building. These examples illustrate that the drawing and the image are distinct, non-interchangeable, are not limited to their physical expression or media type, and a drawing must occur before it is imaged.

However, contemporary practitioners of architecture have called this relationship into question. Frank Gehry has inverted the drawing / image relationship with his Santa Monica Residence. Gehry began this project by experimenting with materiality and wrapping the building at scale, later translating those decisions into published architectural representation. Thus, the Santa Monica Residence, the finished building itself, is the drawing, the full-scale building contains the raw data from which orthographics are imaged then distributed.

Similarly, Peter Eisenman performs an inversion, then a doubling back upon itself, of the drawing / image relationship with House X. Eisenman forces the drawing back upon itself as its own image by intentionally constructing the image as an orthographic object. Thus, the imaged outcome is a drawing itself, which could in turn be used to produce a set of architectural documents retaining all its original raw information. For example, if one were to begin with Eisenman’s orthographic model one could photograph it, trace it, and produce an axonometric on paper. In this case both the documents and product are generative and contain all the raw data necessary to image one or the other, the drawings are the image, the images are the drawing and the relationship between them is folded into one.

However, neither of these examples are stable. If one were to build a duplicate Santa Monica Residence from the images produced by the drawing data of the original full-scale object the result would not be another drawing, it would be another instance, or image, just in a different medium. The actual Santa Monica Residence is the one, and only drawing as that is where the data was generated. Likewise, the simultaneous drawing/image existence of House X falls apart once the physical object is seen from any other angle than straight on, as it is no longer an axonometric with all the inherent data but is simply an image of an axonometric projection in-side view. Recent technological developments, such as AR / VR and 3D Scanning have allowed us to fill these holes, to close the drawing / image loop posited by Eisenman.

This is an image. It is a full set of gcode coordinates extracted from a digital object, which produces an AR model that is 3D scanned, and projected as an unrolled elevation. The raw computational and visual information of the 3D model has been processed and the image is set to trigger the AR object used to produce it, the result is this drawing. The AR object and the printed sheet are simultaneously a drawing and image of themselves.

Works Cited

Ng, Morgan. “An Impression Made on the Ground, Either in Dust or Paste or Snow: Mediums of Architectural Drawing at the Dawn of Paper-based Design.” In Building With Paper: The Materiality of Renaissance Architectural Drawings, edited by Dario Donetti and Cara Rachele. Brepols, 2021.

Unwin, Simon. "Analysing Architecture through Drawing." Building Research And Information 35, no. 1 (2007): 101-10.

Corso, Antonio. "Archaeological Evidence of Drawings of Architecture." In Drawings in Greek and Roman Architecture, 40-47. OXFORD: Archaeopress, 2016. Accessed May 26, 2020. doi:10.2307/j.ctvxrq13g.11.

Luscombe, Desley. "Architectural Concepts in Peter Eisenman's Axonometric Drawings of House VI." The Journal of Architecture: Drawing Today 19, no. 4 (2014): 560-611.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “Architectural Representation I.” Courses. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/architectural-representation-i-fall-2018/

Pérez-Gómez, Alberto, and Louise Pelletier. "Architectural Representation beyond Perspectivism." Perspecta 27 (1992): 21-39.

Schock-Werner, Barbara, and Jill Lever. "Architectural drawing." Grove Art Online (2003). Accessed 25 May. 2020. https://www-oxfordartonline-com.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000003779.

Perez-Gomez, Alberto. "Architecture as Drawing." JAE 36, no. 2 (1982). Accessed May 26, 2020. doi:10.2307/1424613.

Carpo, Mario. "Architecture in the Age of Printing : Orality, Writing, Typography, and Printed Images in the History of Architectural Theory". Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press (2001).

Payne, Alina. “Architecture: Image, Icon or Kunst der Zerstreuung?”. Das Auge der Architektur. Ed. A. Beyer. Berlin: Fink Verlag (2010). 3-39.

Huppert, Ann C. Becoming an Architect in Renaissance Italy : Art, Science and the Career of Baldassarre Peruzzi. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015. 95-145

Difford, Richard. "Conversions of Relief: On the Perception of Depth in Drawings." The Journal of Architecture: Drawing Today 19, no. 4 (2014): 483-510.

Emmons, Paul. "Demiurgic Lines: Line-making and the Architectural Imagination." The Journal of Architecture: Drawing Today 19, no. 4 (2014): 536-59.

Thomas, Helen. "Drawing Architecture". London: Phaidon (2018).

Kipnis, Jeffrey. "Drawing a Conclusion." Perspecta 22 (1986): 94-99. Accessed May 26, 2020. doi:10.2307/1567095.

Drawing and Architecture. Architects Magazine, 1900-1907 7, no. 77 (1907): 95.

Pilsitz, Martin. "Drawing and Drafting in Architecture Architectural History as a Part of Future Studies." Periodica Polytechnica. Architecture 48, no. 1 (2017): 72-78.

Wilkins, Gretchen, Andrew Burrow, Ednie-Brown, Pia, and Burry, Mark. “Final Draft: Designing Architecture’s Endgame.” Architectural Design 83, no.1 (2013): 98-105

Krauss, Rosalind. "Grids." October 9 (1979): 51-64.

Aureli, Pier Vittorio. "How We Became Architects." The City as Project (2017). Accessed 02 June 2020. http://thecityasaproject.org/pier-vittorio-aureli/

Troiani, Igea, and Tonia Carless. "'In-between': Architectural Drawing as Interdisciplinary Spatial Discourse." Journal Of Architecture 20, no. 2 (2015): 268-92.

Benjamin, Andrew, and Desley Luscombe. "Introduction: Drawing Today." The Journal of Architecture: Drawing Today 19, no. 4 (2014): 467-69.

Lewis, Paul, Marc Tsurumaki, and Lewis, David J. Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis : Opportunistic Architecture. 1st ed. New Voices in Architecture. Chicago : New York: Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts ; Princeton Architectural Press, 2008.

Lewis, Paul, Marc Tsurumaki, Lewis, David J., and Lewis.Tsurumaki.Lewis. Manual of Section. First ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2016.

Eisenstein, Sergei M., Yve-Alain Bois, and Michael Glenny. "Montage and Architecture." Assemblage, no. 10 (1989): 111-31.

Scolari, Massimo. Oblique Drawing. The MIT Press, 2012.

Scolari, Massimo. Oblique Drawing : A History of Anti-perspective. Writing Architecture. London, England ; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2012.

Webb, Michael. "On Obeying the Rules." Journal of Architectural Education 65, no. 2 (2012): 20-22.

Galofaro, Luca. "On the Idea of Montage as Form of Architecture Production." (2017) Proceedings 1, no. 9: 870.

Ackerman, James S. “Origins, Imitation, Conventions : Representation in the Visual Arts”. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press (2002).

Holly, Michael Ann. "Panofsky and the Foundations of Art History". Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press (1984).

Panofsky, Erwin. Perspective as Symbolic Form. N. P. (1900).

Pozzo, Andrea. Perspective in Architecture and Painting : An Unabridged Reprint of the English-and-Latin Edition of the 1693 "Perspectiva Pictorum Et Architectorum". Dover Books on Architecture. New York: Dover Publications (1989).

Allen, Stan. Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation. 2nd ed. (2009).

Evans, Robin. “Seeing Through Paper” in The Projective Cast : Architecture and Its Three Geometries, 107-121. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press (1995).

Guillerme, J., and H. Verin. "The Archaeology of Section." Perspecta-The Yale Architectural Journal, no. 25 (1989): 226-57.

Jones, W., 2020. "The Line Connects". [online] Uncube Magazine. Available at: [Accessed 27 May 2020].

Spiller, Neil. "The Magical Architecture in Drawing Drawings." Journal of Architectural Education 67, no. 2 (2013): 264-69.

Damisch, Hubert. The Origin of Perspective. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press (1994).

Benjamin, Andrew. "The Preliminary: Notes on the Force of Drawing." The Journal of Architecture: Drawing Today 19, no. 4 (2014): 470-82.

Evans, Robin. "Translations From Drawing to Building." AA Files, no. 12 (1986): 3-18. Accessed June 2, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/29543512.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design. “Visual Studies.” Courses. Accessed May 8, 2025. https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/visual-studies-fall-2010/